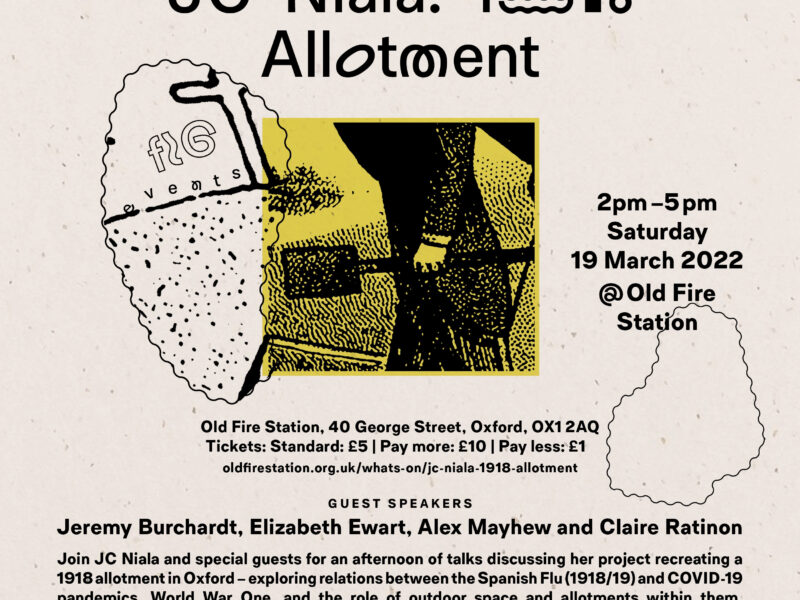

Journal — May 2021

1918 Allotment is a both a living memorial and an invitation to bring a better future into the present. It asks the question – what does it mean to remember a previous pandemic as we struggle to heal in the face of the current one?

Many people have already demonstrated the answer. Unprompted – at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic – people up and down the country began to grow plants in their hundreds of thousands. They spoke of the healing power of caring for something living.

They spoke of the COVID-19 pandemic as though it were a war.

Gardens and libraries are both catalysts for a better world – Sir Paul Nurse: Geneticist and Nobel Prize Winner

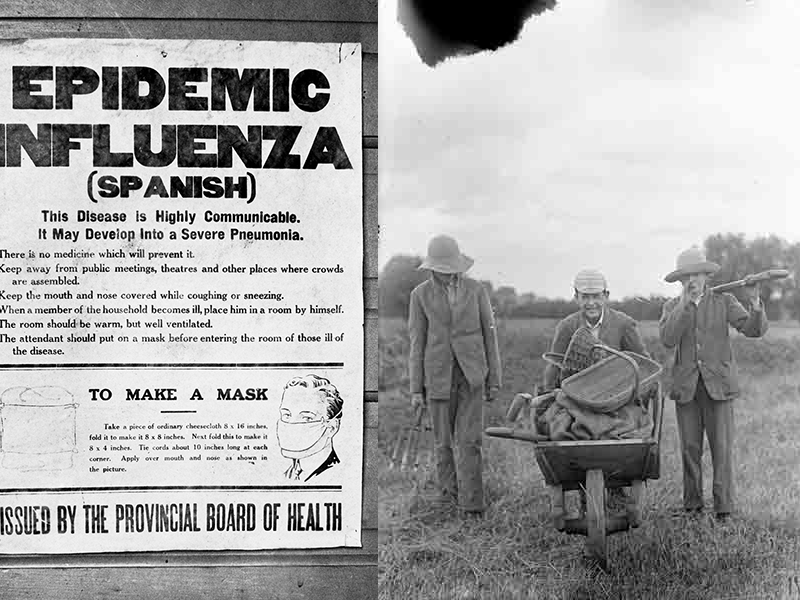

There is a marked difference between this and how the historic pandemic of 1918 was described at the time. Towards the end of World War One, an already devastated Britain faced yet another calamity – the so-called ‘Spanish Flu’ pandemic.

People in 1918 did not use the language of war to talk about the pandemic – because they had just lived through a real one. While it is important to have statues and monuments to commemorate the dead, I have always been curious as to why there are far fewer public spaces devoted to remembering those who support the rebuilding and regeneration that necessarily follows war. Perhaps, unlike life, we see death as a one-off event? In recreating a 1918 allotment this project reminds us that life and death are intimately intertwined.

It honours the ancestors who healed and who are the reasons we are here today.

I think that gardens, and the practice of gardening, challenge the view that death is final. As gardeners, we grow on and with materials that have broken down. The process of decomposition is fuel for the next living thing to grow. Gardeners are obsessed with the process of transformation. We work with both life and death. This is what makes garden spaces both healing and hopeful. Come and experience what it would have been like to grow on an allotment in 1918, when it would have been impossible to imagine life in 2021.

Allotments have always been about more than growing food. They are spaces that have the power to bring together a diverse group of people through their shared connection to the land.

Over this growing season, I will be sharing my research on allotments, pandemics and World War One – through poetry and conversation – with you and the wider public. The plot serving as a reminder and prompt of the possibilities that growing offers us all.