Journal — June 2021

Despite the obvious association, allotments have always been about more than growing food. Keen allotmenteers will tell you that it is a way of life. Political commentators will highlight that allotment history is a case study in the question of land rights. Allotments fall into so many different frameworks because they are gardens and gardens have always been multi-faceted. One of the most powerful qualities of gardens is that they are of the imagination, but they are also real. This is a valuable combination.

A folktale I love is about two soldiers recovering in a hospital. Due to his injuries, one of the soldiers is lying on his back with only a view of the ceiling. Unsure that he will make it – he tells his roommate that he has lost the will to live. In response, his roommate begins to tell him every day about the view outside their window, taking care to describe the garden in great detail. He talks of the trees and the flowers and describes the birds that come to visit even though they can’t hear them. The soldier begins to heal. One night, his roommate tragically succumbs to his injuries. The following morning, distraught, the remaining soldier asks to be carried to the window so that he can look out into the garden in memory of his friend. The nurses inform him that their room has no window.

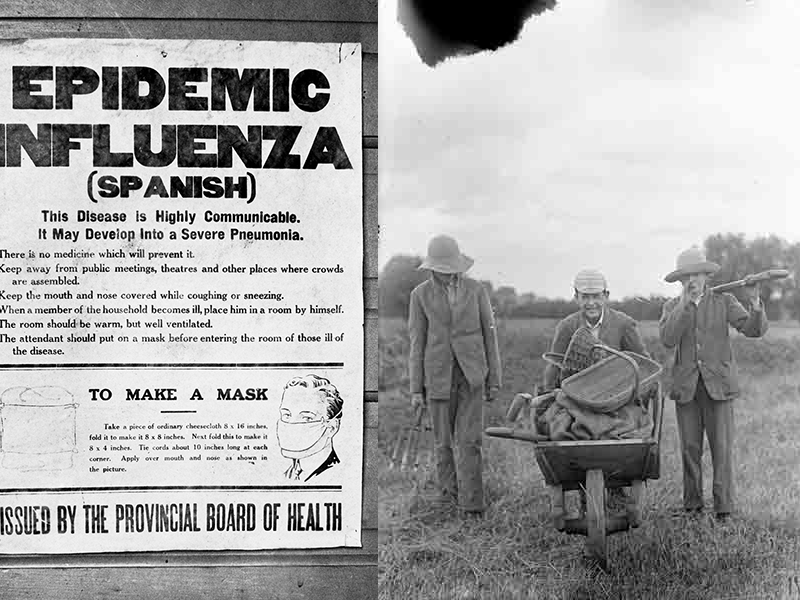

Gardens as sites where the circle of life and death plays out seasonally have always been places where healing happens. Allotments are no exception. Although World War One is characterised by the bloody battles in the trenches, soldiers also had a life away from the front line, in spaces in which plants were essential. A collection of letters and ephemera held at the British Library, as well as accompanying trench journals (the newspapers produced for soldiers on the front line) reveal a fascinating account of the British Expeditionary Forces’ allotment culture.

It’s no secret that one of the biggest complaints that soldiers had about life in the trenches were the rations and quality of food. As well as to steel their nerves – it could be argued that their daily 5:30am tot of rum was a necessary ingredient in helping to make their food more palatable. And with good reason, the biscuits provided were so hard that soldiers routinely carved mementoes including items like picture frames from them. In that context it would be easy to surmise that the allotment gardens cultivated by the forces in the French town of Le Havre were to supplement army supplies of food. However, looking through the collection, it becomes clear that the allotments were also good for the soldiers’ mental health, at the very least by providing an amusing distraction. In 1917 and 1918 there were competitive vegetable shows held at Le Havre. These were akin to the traditional ‘Annual Show’ held on allotment sites across the UK, and that still take place today.

‘Soon the spring will drop flowers’ — Richard Aldington, War Poet, ‘In the Trenches’, 1948

A more direct example of what came to be dubbed therapeutic horticulture can be seen in a photo in the Imperial War Museum’s collections. It shows a vegetable garden at the No. 1 Convalescent Camp in Boulogne. It was taken on 6 October 1916.

The allotments and gardens I have described are far from an exception. One of the trench journals named The Spud gave advice on fundamental aspects of gardening such as digging. Twentyfirst century allotmenteers would also recognise the allotment culture that was practised, complete with the swapping and sharing of tips, seeds and tools.

Given the similarities between allotment culture today and the World War One allotments, I feel that I can draw some comparisons with why the soldiers must have found them healing to work in. During the COVID-19 pandemic, people turned in their droves to growing, and cities like Oxford which previously did not have waiting lists on many allotment sites suddenly found themselves full. When I spoke with my fellow allotmenteers they talked about the special shift in time that takes place on the allotment. I have experienced it myself many times. Engrossed in an activity, it’s easy to lose all sense of time and enter into another world entirely. Thinking of the plants’ needs is an invitation to nurture with the pleasing anticipation opportunity that your care can bring about life. Surrounded as they were by death and destruction – it is not difficult to see that the men of the British Expeditionary Forces would have cherished the healing opportunity to engage with the fruitful end of the life cycle when their jobs compelled them to be intimate with all things finite.