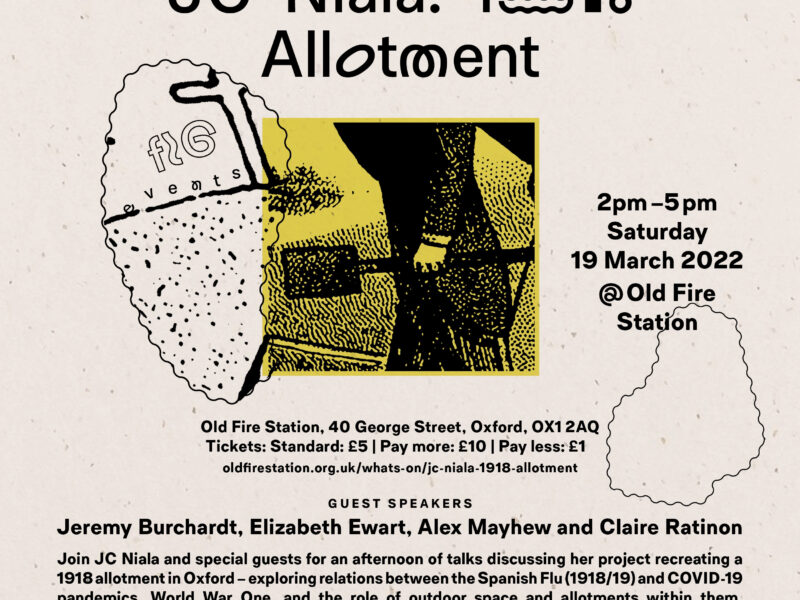

Journal — June 2021

“Modern life is, for most of us, a kind of serfdom to mortgage, job and the constant assault to consume. Although we have more time and money than ever before, most of us have little sense of control over our own lives. It is all connected to the apathy that means fewer and fewer people vote. Politicians don’t listen to us anyway. Big business has all the power; religious extremism all the fear. But in the garden or allotment we are king or queen. It is our piece of outdoors that lays a real stake to the planet.”

― Monty Don, My Roots: A Decade in the Garden

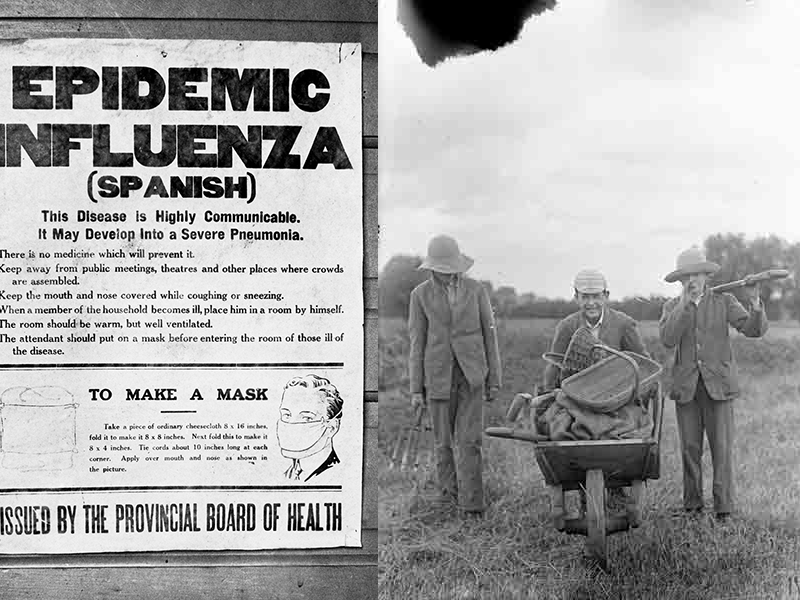

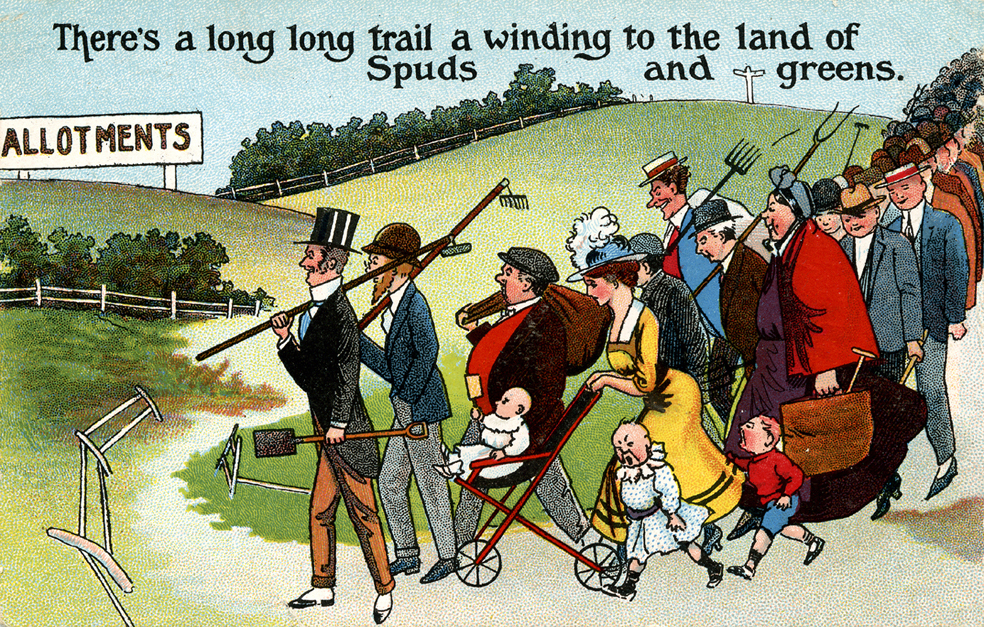

While it true that there were more men growing on urban allotment sites at the beginning of World War One, by 1918 this had changed. As with jobs and other vacancies created when men went off to fight in the war, women stepped up and became involved in the much-needed food production. This, however, was not a smooth transition. Allotments were very much a male domain. There are still traces of male design on allotment sites today by way of the lack of toilet facilities.

While carrying out research on allotments in the first couple of decades of the 20th Century, I found the terms in which they were seen to be quite clear. Church officials, wealthy landowners, government bureaucrats and so on saw allotments as their responsibility to provide the ‘deserving poor’ access to land to grow their own food. They also saw them as a way of keeping the ‘n’er do wells’ out of the ale houses and engaged in more wholesome activities that would give to, rather than take from, their families. There is even correspondence from wives of wayward men to the Vacant Land Cultivation Society begging for an allotment to improve the situation in their household. In at least one case, follow up correspondence shows that social improvement by way of allotment gardening did work, and housekeeping money reappeared and was accompanied by fresh fruit and vegetables.

All this led to the relatively accurate stereotype that the typical allotmeneteer was a white working-class male likely holding up his trousers with baler twine. Yet, throughout allotment history (certainly from 1918) this was not always the case. Allotments have always had an element of diversity which has only continued to grow since 1918. An example of allotments run by wealthy businesspeople that navigated the transition to include women are the allotments set up by the Rowntree family. This Quaker family, as equally known for their promotion of social reform as their confectionary, formally offered women permission to be allotment holders in 1917.

Even before the commencement of women plot holders, there was a certain amount of diversity of allotment holders’ social class. Allotment rents were far closer to market land rates than they are now and there were people who may not have been wealthy but had enough money to rent one and certainly did not want to be seen on the receiving end of ‘charity’. By the end of the World War One in 1918, both these types of allotment holders, despite returning soldiers, were not going to give up their allotments.

Instead of displacing ‘the ladies’―the Rowntree family gave over more land to returning soldiers ensuring that ‘the ladies allotments’ continued. Other Quaker business families such as the Cadbury’s in Bourneville, Birmingham (yes, the chocolate is named after the model village of the same name) also provided allotments for their workers. In general, in fast-growing cities such as Birmingham, Sheffield, Oxford and Nottingham to name a few – allotments became popular and drew growers from a variety of working lives including tradespeople, grocers and even the odd medical professional.

Allotments went on to reflect (and surpass) the diversity of the urban communities that surrounded them such that by the 1970s, it was not usual for allotments to have a broad range of people of different countries of origin and social backgrounds. These ‘newer’ allotmenteers brought with them seeds from around the world. Their growing on allotments enabled them to do many things. First of all they were able to grow things that they liked to eat (food from their culture), by growing on English soil they were able to ‘re-root’ and form a deep connection to their new country. Finally even though they were ‘re-rooting’ they were also maintaining a connection to the ‘old country’ through the food they were eating. This also benefitted the world outside the allotment gates as food such as garlic which we now take for granted were gently introduced into English cuisine. The ‘old boys’, as stereotypical allotmenteers are affectionately known, were still present but were no longer always the largest demographic. For one thing in 2020, women allotmenteers across the country, outnumbered men.

Apart from the war, another underlying change to the increase in women on allotment sites was linked to enfranchisement and the ability to vote. The next post sheds light on the ways in which securing the right to vote is intertwined with access to growing land. Monty Don is right when he wrote about the ways in which being able to cultivate one’s own piece of land can make kings and queens of us all.