Journal — June 2021

There are two distinct responses I get when I tell people that I am developing a 1918 allotment. Non-allotmenteers usually remark on how ‘cool’ that is. Allotmenteers immediately want to know what I am going to do about ‘bugs’.

The answer is simple – cheat.

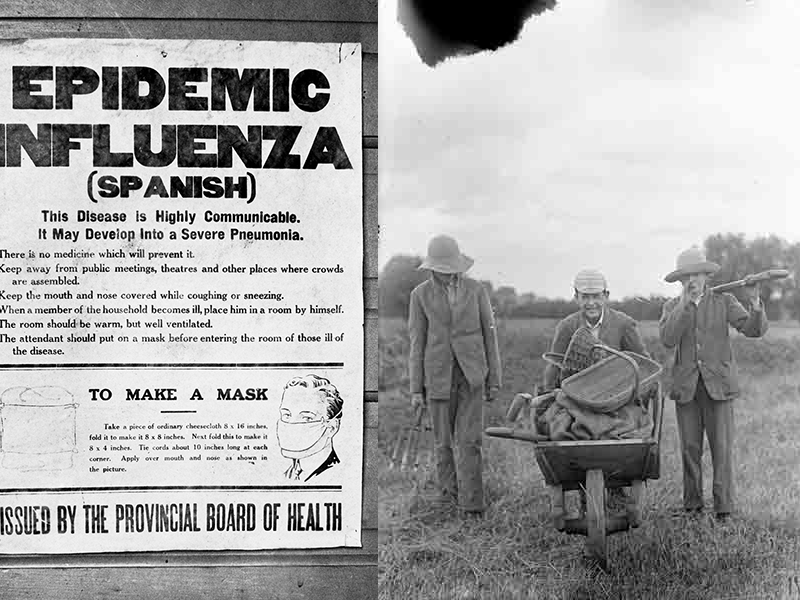

It is one thing to create a memorial by planting heritage seeds and eschewing the use of plastic. It is quite another to create a memorial by contributing to the death of living creatures. Although (for some people) pesticides are no longer directly linked to it – they are in effect another product of World War One. The metaphor of battle that can characterise human interactions with nature – in particular when we are trying to control her – is unhappily real when it comes to some of the substances that we have used on our plants and ourselves.

My interest in pesticides, and in what exactly they are, intensified after I was tear gassed over a decade ago. Prior to having been on the receiving end of it, it sounded just the right side of innocuous. Onions, for example, can make one tear up but then no matter how unpleasant it passes relatively quickly and with no lingering side effects. My opinion changed entirely once I experienced it directly. The burning on my eyes and skin, gagging and tearing that followed was awful. I also recognise that I am lucky to have had no lasting effects.

Around the same time, I was attending an organic gardening course. Not all the course participants were convinced by the dishwashing liquid and chilli concoctions that we were learning about to protect our crops from pests. When our course instructor referenced chemicals – having been recently tear gassed – the penny dropped. Tear gas is a form of chemical warfare that is from a wider family of gases initially used by French soldiers to force their German counterparts out of trenches that has now made its way to city streets.

I cannot help but find it alarming that substances that were first used on battlefields have now spread around the world to be used against civilians. From, the U.S. where the police used it on unarmed Civil rights activists to the U.K. where it has been used since the 1960s.

“Unless you destroy all the Insect Pests on your allotment, they will assuredly destroy your crops. You can’t afford at the present time to grow crops for insects to consume.” — Allotment Holder’s Enemies, 1918

All across Europe there are poets (who were also soldiers) like Wilfred Owen who survived World War One and wrote about the horrific effects of the different types of nerve gasses that were used against human enemies. The words of the Belgian poet-soldier Daan Boens from his 1918 poem simply entitled Gas are especially moving:

The stench is unbearable, while death mocks back.

The masks around the cheeks cut the look of bestial snouts,

The masks with wild eyes, crazy or absurd,

Their bodies drift on until they stumble upon steel.

The men know nothing, they breathe in fear.

Their hands clench on weapons like a buoy for the drowning,

They do not see the enemy, who, also masked, loom forth,

And storm them, hidden in the rings of gas.

Thus in the dirty mist, the biggest murder happens.

The horrible truth is that many commercial insecticides are variations on a theme of chemical neurotoxins. Substances designed to destroy pests through their nervous system and tailored to insect or human targets.

The connexion between wars against peoples and other types of nature is one that has already been drawn by historians. The historian Edmund P. Russell says that they are impossible to separate and that metaphor, or science and technology relating to the human ability to destroy, muddles distinctions between human and insect enemies. We are all part of the same wider nature and war is war. It is perhaps not surprising that ex-soldiers who turned to allotments on their return home were not squeamish about the use of arsenic to poison caterpillar grubs on fruit trees.

And yet I also find it difficult to judge the 1918 allotmenteers harshly. The levels of poverty and hunger at the time were staggering and many allotmenteers were thus involved in a life and death struggle with the insects on their plots. The silent short (4:36) film Allotment Holder’s Enemies produced by the Smallholder magazine (which started in 1910 and is still going) gives a flavour of the received wisdom of the time about how best to handle pests. You can watch it for free here.

I am sure that 1918 allotmenteers would think that I was at best entitled, and at worst insane, if they knew that instead of pesticides, I work with (amongst other organic methods) the idea of ‘sacrificial plants’ – indeed plants grown for the insects to consume. So, I am cheating and there will be no artificial pesticides used on the 1918 allotment. We will, however, try some of the more natural methods also recommended from that era. Living in a time of relative peace, I feel lucky that I can attempt to collaborate rather than enter into combat with the insects who also share the plot.