Journal — June 2021

One of the most common reasons people state for having an allotment is that ‘they like being outside’. Many even state this as their primary reason – over and above growing plants. They are onto something. There is increasing evidence that growing on an allotment is good for one’s mental and physical health but pinning down exactly what it is about allotment growing that is so good, is much more complicated. Perhaps it’s because the answer is so obvious it tends to get-overlooked:

Simply being outside.

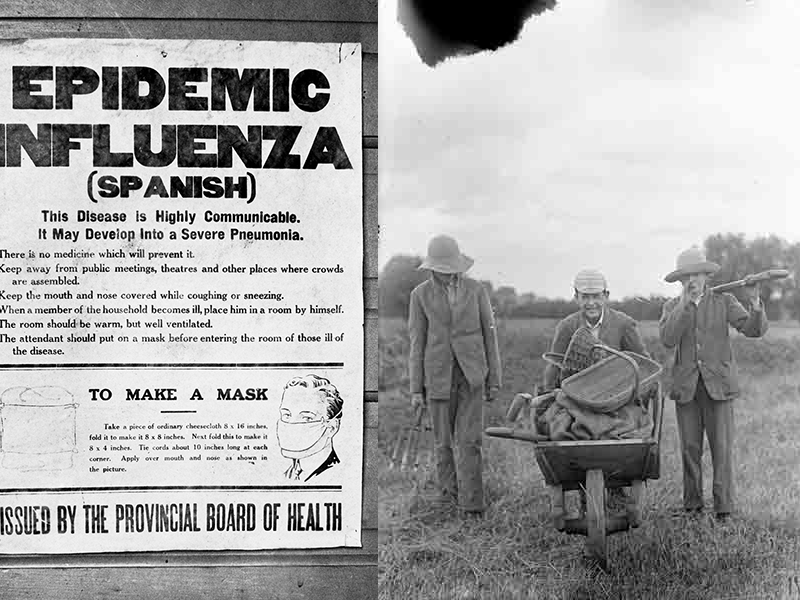

During the 1918/1919 pandemic when it seemed like there was nothing that might be able to combat the spread of the H1N1 Virus, the ‘open-air’ method provided a lifeline. Particularly when combined with meticulous hygiene and face masks, deaths were substantially reduced for some patients. In cities like Boston in the US, open-air hospitals were particularly effective and increased survival rates for any sick person who was lucky enough to be admitted to one.

It is not only hospital doctors who are aware of the benefits of being outside. Many allotmenteers are very aware of this as well and self-prescribe ‘open-air’ therapy even if they may not refer to it as such. As I was carrying out my doctoral research on three different allotment sites in Oxford during the current pandemic, I certainly saw plenty of people administering their own ‘open-air’ or preventative medicine. Allotment sites were a salvation – especially for those who lived in flats.

“Live in the sunshine”

– Ralph Waldo Emerson

On one site a family turned their plot into a miniature open-air home complete with sofa and drinks cabinet – the part of the plot on which they were growing serving as a replica home garden. It turns out that researchers have found it easier to pin down what is beneficial about being outside than to find out why allotmenteering is good for you. For one there is the increase in Vitamin D levels. Vitamin D is key to fighting disease and has been shown to reduce the likelihood of developing the flu. It also helps to regulate mood and can be used in treating depression.

In a startling tale of survival, a British soldier named Patrick Collins successfully treated himself in 1918 by making ‘open-air’ therapy central to his cure. Noting early signs of influenza, he dragged himself away from his regiment, administering only rum until he had sweated it all out over several days. He was only one of a few from his regiment not to die.

Somewhat surprisingly this effective ‘open-air’ method that allotmenteers partake of, has been resisted throughout history. Even as ‘the science’ catches up to explain what allotmenteers know – allotmenteers being ‘experts by experience’ – governments across Europe have been slower still to respond to its benefits. During the current pandemic, not all allotments were able to carry out their straightforward health measure of ‘being outside’. In England, during lockdown, allotmenteering thankfully was legally allowed as part of the daily hour of exercise but this was not the case in France or Ireland. There, allotments were locked and allotmenteers faced the double whammy of being restricted from the health benefits of ‘being outside’ as well as a reduced access to their own grown food.

If there is a lesson from history – it is that wisdom can lie apparently in the simplest solutions. While in my next blog post I will look at what allotments reveal about social class both in 1918 and during the current pandemic… it is worth considering now that the vast majority of people in the UK (around 80-85% according to Friends of the Earth) has access to some green space, whether it is a public park or wood, an allotment, garden or other outdoor space such as fields or a balcony of plants. What allotmenteers have shown us is that we have a powerful possibility to improve our health that begins the minute we step out of our box.