Journal — September 2021

It was completely unexpected – on the 14th of August 2021 during the annual Elder Stubbs Allotment Festival & Vegetable Show – the 1918 Allotment won ‘Best in Show’ for our produce. It is now easily one of the things of which I am most proud. Allotment competitions and prizes have a history as long as allotments themselves and are a community focal point. Usually accompanied by live music, produce auctions and family friendly activities, they also provide the local (non-allotmenteering) community an opportunity to experience of allotment life.

I also think that allotment competitions offer allotmenteers the opportunity to fulfil their curiosity about what (and how) other people are growing without being intrusive or rude. Most people who garden on allotments enjoy having time and space to themselves and so there is a measured type of sociability that occurs on the site. People are happy to engage with each other but mainly at a distance and for as long as it does not eat into too much of their precious cultivation time. An annual competition is a good excuse to look at what other people have been growing as well as to engage in friendly competition.

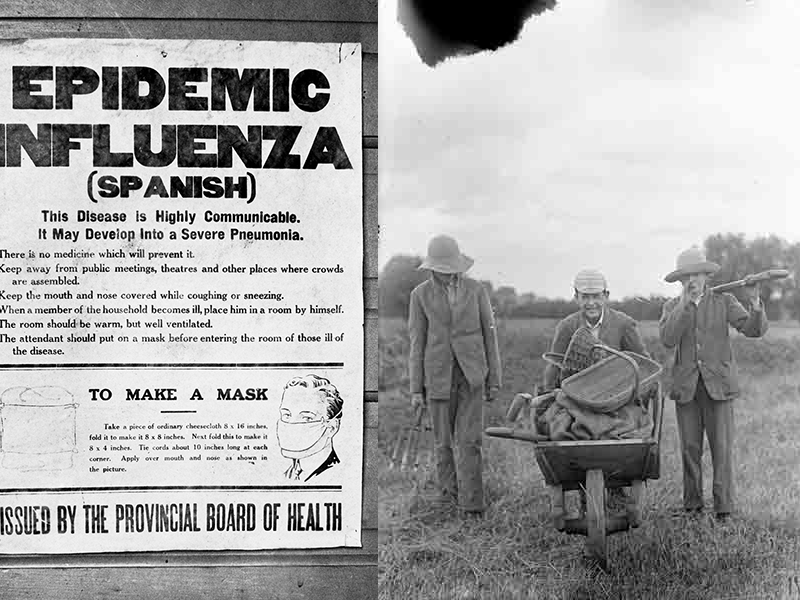

Some of this stems from the recreational aspect of allotmenteering which is less foregrounded. Even during times when it was assumed that people were primarily allotmenteering in order to grow food – there are clear signs (such as flowers grown for beauty) that there has always been an aspect of growing for the pleasure of it. Or as the World War One trench journal The Spud described gardening on allotments during the war – it was something done as a ‘rest cure’. Even today, there are studies that show the benefits of gardening on mental as well as physical health.

What particularly interests me is this tension between the individual and the social. There is a special atmosphere when one grows alongside other people – albeit on individual plots. There is the sense of being part of a wider community even if you practise by yourself. This loose connection is strengthened by communal moments, and allotment vegetable shows and competitions are a part of it. There are many different prizes that are awarded at these competitions, which are a delightful mix of being taken seriously enough for judges to come from other sites (to prevent bias) and for winning cups and shields to be presented, but are also ultimately seen as a good excuse for people to get together over their passion. A question that I have had since the outset of my research is why there is always a prize for the biggest of different types of vegetables. The unanimous answer is that it is about ‘fairness’ and having a practical measure that is relatively easy for all involved to agree on unlike for example – the tastiest tomato. I suspect that this idea has travelled through time and large vegetable size is one of the measures that does fall into the category of being taken seriously. So much so that during a World War One Vegetable Show in 1918 a large vegetable was reported to have been stolen in the run-up to show and likely even displayed by the thief so that they could win!

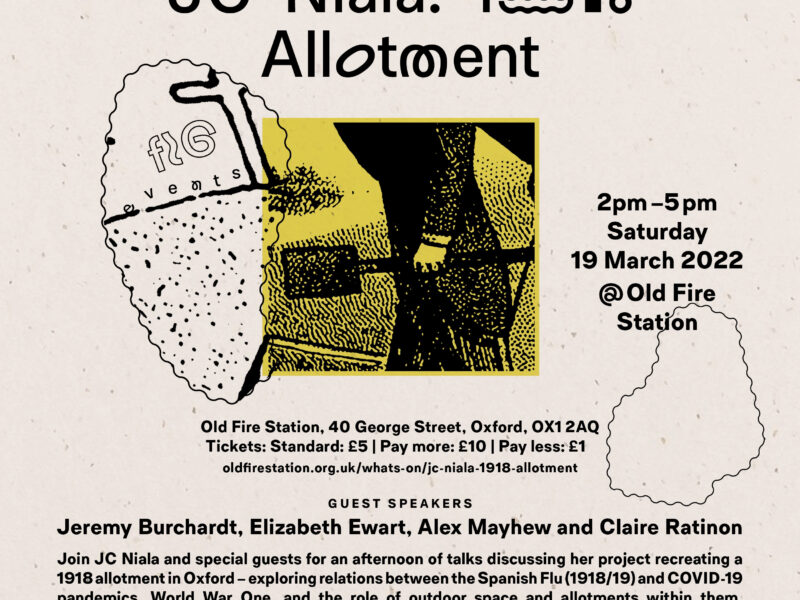

Prior to recreating the 1918 Allotment – I would have been too shy to enter a vegetable show but thanks to Sam’s enthusiasm on the 14th August 2021 we did. There was an echo to times gone by, as on the 14-16 August 1918, during World War One and the 1918/1919 pandemic in Le Havre in France, the British Expeditionary Forces held an immensely popular vegetable show for the second year in a row that featured produce from the allotments that had been tended to by Australian, Belgian, British, Canadian and Chinese troops. French civilians and German prisoners of war also participated. The British Library holds a fascinating collection of the ephemera from this event that was attended by 11,000 people.

One of the awards (won by German prisoners of war) was for the most productive plot. They managed to produce 26 tons of vegetables per acre which speaks to their level of skill. By way of comparison – experienced farmers can achieve yields from 16 to 28 tons per acre. Their rates of production contrast greatly with a complaint raised by an experienced allotmenteer I spoke with during my doctoral research about some of the allotmenteers she observes these days: ‘They don’t pick and eat’, she lamented.

Because of the challenges on people’s time, their day-to-day lives can be out of step with the changes that are happening on the plot. Maintaining a productive plot requires working with the rhythms of the plants and wider nature in order to respond to them in a timely manner. I have written in a previous blog about working with T.W. Sanders’ book Kitchen Garden and Allotment, which encourages high levels of production. The idea being that as soon as a particular crop is ready for harvesting, it should be used and the next crop ready to go in. Much as we aimed for this on the 1918 Allotment – the practice is a challenge to achieve. What also happens is that one gets so completely immersed in the processes of cultivation from ground to table (or farm to fork) that it can be easier to recall the failures than to take note of the successes along the way. There is nothing like having your hard work recognised by your peers – which is why the vegetable show prizes are so meaningful. They also get noted down and so it feels good to be part of a tiny piece of a site’s allotment history.