Journal — May 2021

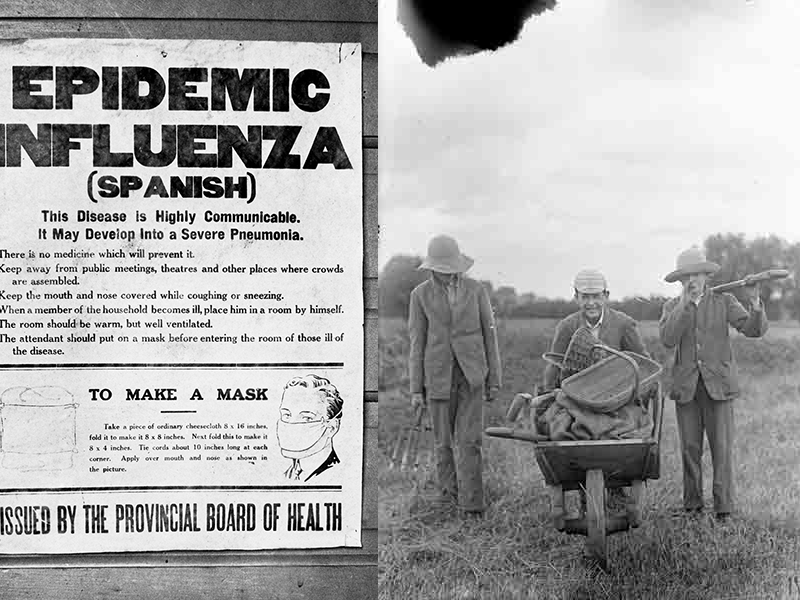

The thing to escape from that is being referenced in this newspaper article is the 1918-19 influenza pandemic. There are many parallels that have been drawn between the 1918 and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. They both travelled around the world at a frightening speed, leaving appalling numbers of fatalities in their wake. During both pandemics, the government public health messaging on the benefits of hygiene sharply increased. And people up and down the country turned to growing plants to improve their physical and mental well-being

What is less discussed are the differences. The fact that the 1918-19 pandemic followed World War One, meant that the way in which the pandemic was discussed was markedly different to the current public conversation.

On 24 March 2020, when I received the government text message informing us that ‘New rules are in force now’, my immediate instinct was to gather my gardening equipment and jump into the car to go and check on my allotment plot. Cultivating on an allotment site during lockdown counted as part of the allowed daily hour of exercise, in part because of a change in legislation that can be traced back to the 1960s (which I have written more about here). Arriving at the site, despite the difficult circumstances, I burst out laughing.

I realised I had made the short 10-minute drive to my plot because I was somewhat worried that something might have happened to her (yes, my plot is part of Mother Earth and so very much ‘she’). Nothing had happened to her. I was the one who was worried and concerned about what the lockdown meant. My plot was there, much as she always is, in need of some attention, but otherwise doing what it is she does best – which is just to be.

I slowed down and took a deep breath.

Over the next year, as I worked on my plot and adjusted to the new life of lockdowns, easing and further lockdowns, I thought about growing. Like many people around the world, I also thought about life and death. When Sam, the curator from Fig, approached me about a commission – I immediately knew what I wanted to do. I wanted to cultivate a 1918 allotment. 1918 was a pivotal year in British history. The Great War was finally ending, but was instead replaced by another tragedy – the so-called ‘Spanish Flu’.

The conscientious allotment holder stands a better chance of escape than his sedentary neighbour – The Daily Mail, 25 June 1918

In 2020, I noticed that there were two things happening simultaneously as people struggled to find ways to cope – they were sharing poetry and growing plants. Because I was thinking about 1918, I turned to the poetry that had made a huge impact in my life – war poetry. I thought a lot about the poem ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’ by Wilfred Owen. NHS and other key workers were described as being ‘on the frontline’. The government rhetoric might have been seen as a way to encourage their arduous work, but the lack of PPE and impossible conditions meant there were those who felt uncomfortable to have their actions called heroic. Wilfred Owen in his poem says it is an old lie that ‘It is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country’. For African people there was the startling observation that the most vulnerable medical staff were people ‘like me’. As an anthropologist I could also not help but question – was it easier here in the UK to use the metaphor of war because we live in a time of relative peace? And with climate change in the mix of emergencies – what does it mean to be at war with nature?

I returned to present day and historical allotment sites to try and find some answers. It turns out that soldiers grew plants in World War One trenches and that upon their return allotment sites and other gardens were mobilised as places to heal. I became both thankful for and interested in the people whose actions meant that it is possible for me to cultivate on an allotment site today. My research has taken me from 1918 English cultivation classic books to bees that stopped a World War One battle on the East Africa coast. A quiet thread through all that I uncover is our enduring ways of dealing with uncertainty. Even as the 1918 allotment develops, and we begin to take bookings for people to come and visit it during the summer – for poetry readings and in conversation events – I don’t know if the plants on the plot will grow or whether they will survive the weather and pests. Yet the possibilities that each seed holds continues to give me hope, as they have done to many growers over a century and more.