Journal — June 2021

Discovering Elder Stubbs

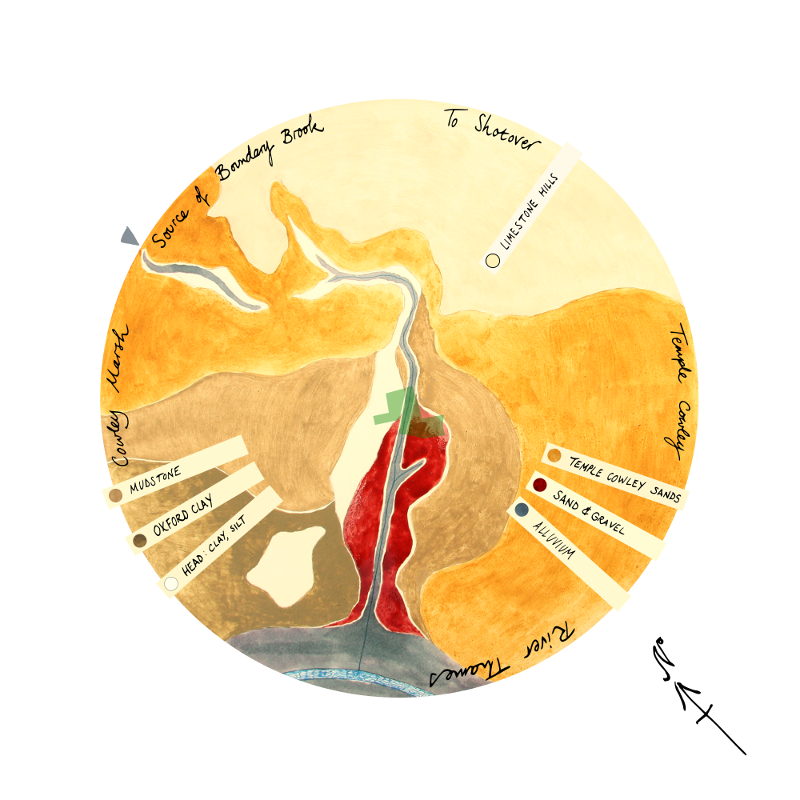

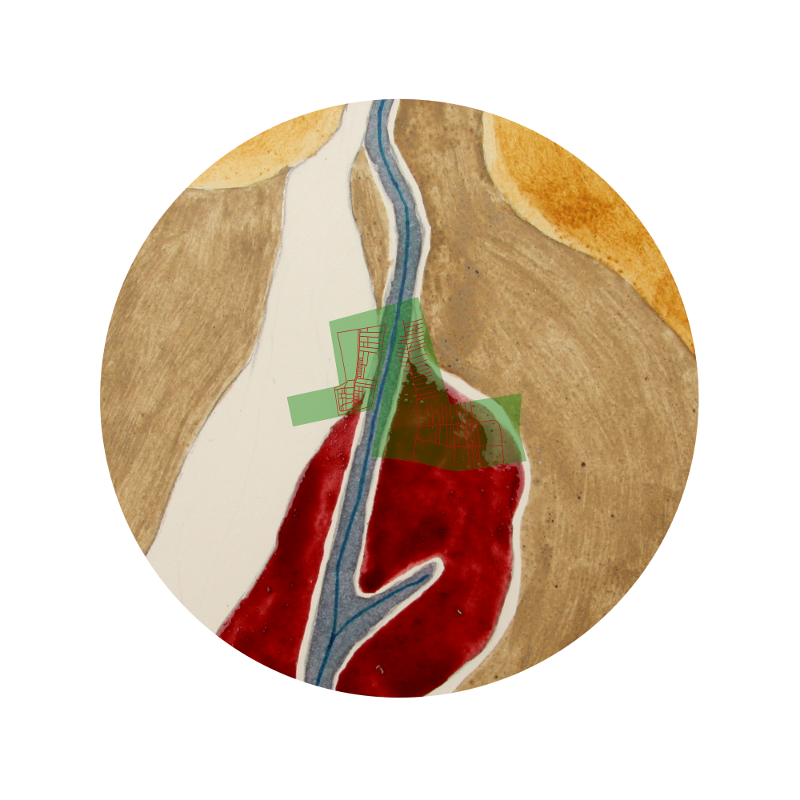

On the brow of limestone hills, a spring emerges. Wandering down toward the Thames, the water becomes Boundary Brook – named for its former role as outer boundary of Oxford city. Along the course of this brook alluvial green spaces hang like beads, among them Elder Stubbs allotments. This floodprone area, left out of medieval field systems, was dedicated at the time of enclosure for allotments when local people were turfed off common land further up the hill. A certain sad reference to a lost past is present in the name, Elder Stubbs. It refers not to trees on the present site, but is a borrowed name from the old Common. Presumably elder trees once grew there – nobody really knows [1].

At the start of this first Fig project I find myself standing on the bare new allotment plot and looking about. On this site and the places within about a mile roundabout I will conduct my research project. ‘Elder Vernacular’ will ask what a visual art practice might look like if it took this place and these times deeply to heart.

I begin at a time of Covid induced nearby-ism, which dovetails with responses to the climate emergency and is urging city dwellers and artists like me en masse toward the adventure of rediscovering the local. I watch Youtube videos of millenials earnestly seeking out their nearby places. A man scrabbles about in a brook looking for clay. A woman makes jewelry from found scrap. We wander the contemporary landscape “like hunter-gatherers searching for bits and pieces of meaning” [2].

No Such Place as Away: Searching for a New Vernacular

Is such a thing as vernacular style possible or relevant today, as one answer to the questions posed by contemporary events to all creative people? ‘Elder’ here speaks not just to the trees but also to the Elders who knew, who know and who keep knowledge alive. I will be seeking out some of these wise ones, hoping to learn. The term ‘vernacular’ brings with it notions of yearning for groundedness and local autonomy which is the shadow of industrial modernism; a shadow perhaps grown larger than ever and threatening to return in full force. Searching for the vernacular involves by nature a problematic, nostalgic “longing for a home that no longer exists or has never existed” [3], the critical seeking-out of which might nonetheless offer clues to the future. There was once, for example, a vernacular Cowley style in ceramics – developed from local materials, not by ‘locals’ but by the Romans, and with extensive trade links. A cosmopolitan vernacular. Such a vernacular today will acknowledge its problematic status amidst late capitalism, and whilst in love with physical proximity it will not reduce questions of identity to single places, divorced from others or relying on arbitrary outsides for its sense of self. As recycling advocates say, “there is no such place as away”.

And we can take this concept further, looking not just at how we meet our material needs but our emotional ones too. We can look at those places which art has tended to designate as “away”, not to be acknowledged. The notion of congruence might be a useful one here: a psychological term meaning conscious awareness of all present experience. That includes the difficult and uncomfortable parts; the parts we are tempted to deny and push away. For artists this often includes the sources and ultimate destinations of our materials. Perhaps too it includes the denial of reciprocity and vulnerability which are the essential “away”/”other”/”outside” in the narcissistic quest for success. A culture of incongruence should concern artists, who are by nature communication workers. Where incongruence is present, “ambiguity or contradictoriness of communication” is the result [4]. When artists strive to do “the work that reconnects” [5] and yet deny to awareness the uncomfortable facts of how our practice functions, our art cannot speak wholeheartedly. The Fig plot, grounded in one place and amongst other living things, could perhaps be one site around which to rehearse another way.

This journey of discovery begins at an interesting time for me, having spent the past few years working in mental health. This work has taught me that good health is equivalent with groundedness in the present place and time. This groundedness calls for the often painful abandonment of fantasies hungover from other places, other times. Such leftover fantasies if unchecked tend to result in the frantic pursuit of ideal forms, unrelated to present conditions. The ecological parallels are clear. In this spirit I hope through my journey to search out a different way of being as an artist, allowing materials to emerge from places and relationships in a grounded way. This transition, by its nature, entails loss and grieving. Facing up to the fact that today’s art will be tomorrow’s compost. Everything ends up back in the soil. The question is what kind of compost we will be digging in for those who come after us.

[1] John Purves, ‘Notes on the History of Elder Stubbs’

[2] Robert L Thayer, ‘LifePlace: Bioregional Thought and Practice’

[3] Svetlana Boym, ‘The Future of Nostalgia’

[4] Carl Rogers, ‘On Becoming a Person’

[5] Joanna Macey & Molly Brown, ‘Coming Back to Life’