Journal — March 2022

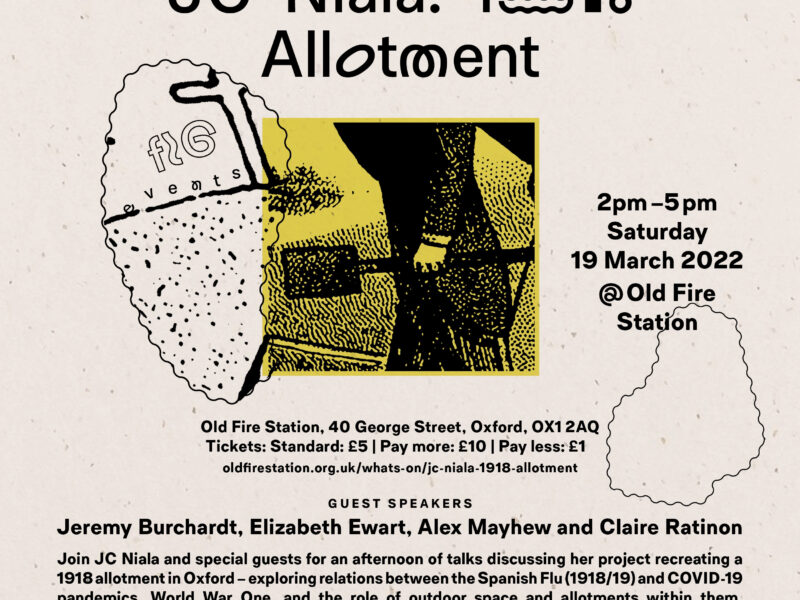

The act of growing never fails to bring about connection. Some of these are to be expected, and others are less immediately obvious. On Saturday 19th March, a large group of people from a wide range of backgrounds, ages and places filled the theatre at the Old Fire Station in Oxford to hear from Jeremy Burchardt, Elizabeth Ewart, Alex Mahyew and myself. I opened the discussion event with an introduction to the esteemed panel whom I referred to as my ‘living library’. They are all people whose work has had a profound impact on my own and I was excited that they agreed to spend an afternoon with me thinking about all things growing – with allotments, war and pandemics as bouncing off points.

Jeremy Burchardt is an allotment historian who brought to life the surprising histories of allotments from the 1700s onwards. He demonstrated the ways in which although there was a critical aspect to alleviating poverty by way of access to food – allotments have always been about much more than growing food. Allotments are spaces where families engaged with each other and were critical in aspects of wider wellbeing. He also spoke about their specific role in crises and ended with the wonderful provocation of allotments as chameleons – the reason that they have been able to survive so long is precisely because they adapt to the needs of those who cultivate on them and are never static in their manifestations.

He was followed by Elizabeth Ewart who took the audience to two contrasting and yet somehow similar places in the world – the Ethiopian highlands and low land South America. In each of these places are communities that have a profound understanding of what it means to live ‘the good life’ as they do so in their stunningly beautiful gardens. The Panará peoples in Brazil cultivate geometrically shaped spaces (whose impeccable patterns are best viewed from above) and form intimate and complex relations with the land. Enset (also known as false banana) in Ethiopia is a drought resistant crop that defies industrialised measures and therefore exists in a landscape and amongst peoples who support its diversity to make for a caring and connected way of life.

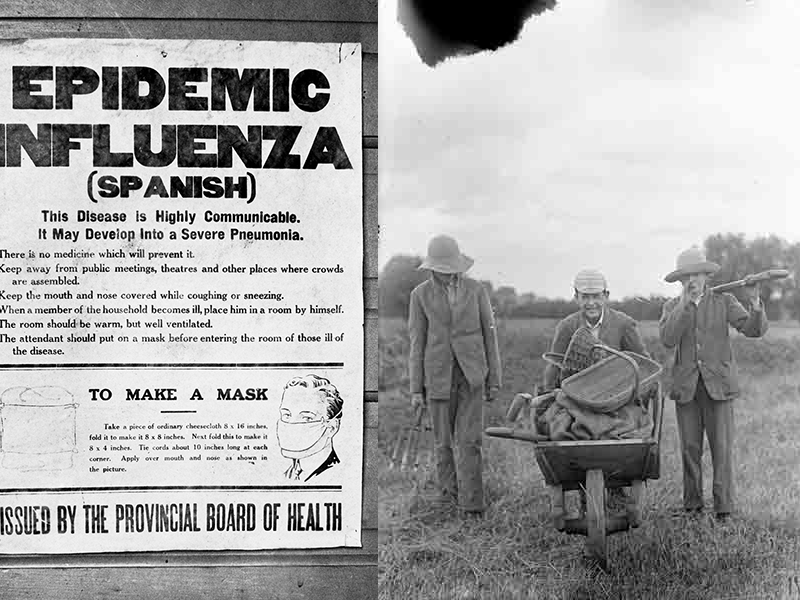

This idea of connection was picked up by Alex Mayhew but in a different context. Examining allotments in the First World War’s Western Front, Mayhew showed the ways in which vegetable competitions brought about a certain levelling of otherwise rigid military hierarchies. Colonel and corporals arranged for the shows together and were involved as equals in their planning and execution. Allotment gardens did not just supplement much needed food but also developed relations across the lines, mitigated boredom and even signalled forms of resistance, with barbed wire being deployed in ways that were not directly related to purposes of war. His talk added another layer of complexity to what it means to grow in unexpected places.

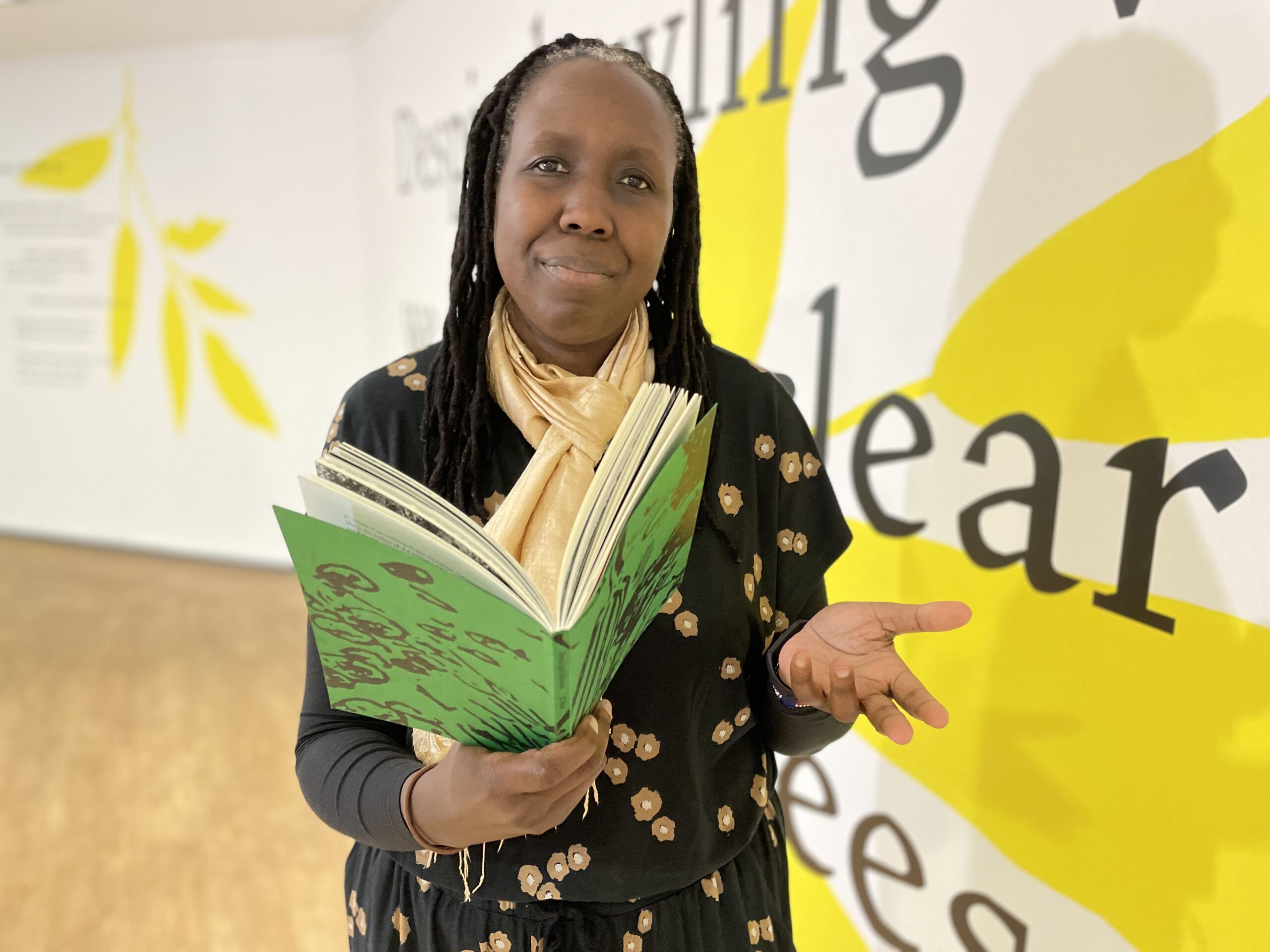

In what was perhaps the most personal of the talks, Claire Ratinon, an influential organic grower, highlighted what it is to grow in soil that is not immediately welcoming. Ratinon has Mauritian heritage, which bears a history of enslavement and indentured labour that makes her all too aware of the meanings of labour in agriculture. Who has access to land? Who controls the access? How different bodies are received when they eventually engage with the land in question. She reminded us all of the humbleness of the act of engaging with nature by growing on and with it.

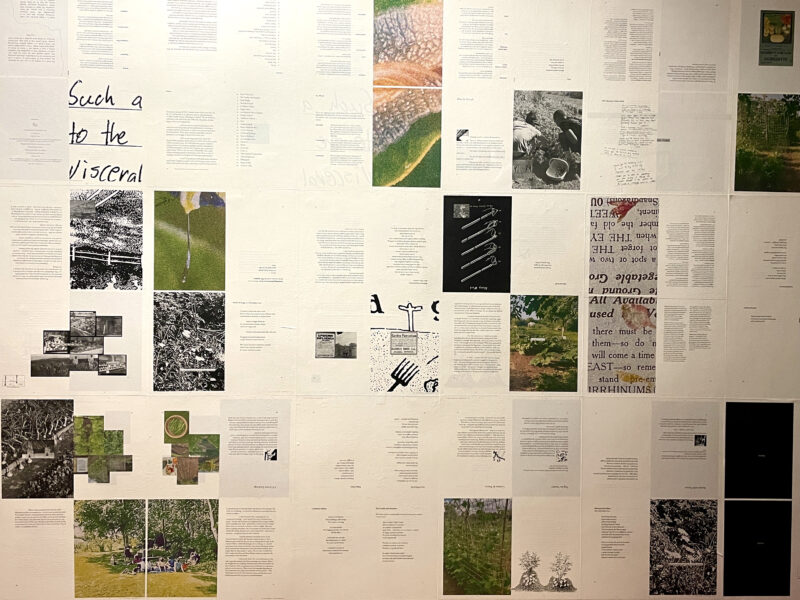

Her use of the word humble resonated deeply with my own feelings when I reflect on the year that has been the 1918 Allotment project. I have been so generously supported by Sam of Fig; TORCH; Arts Council England; my department at the School of Anthropology and Museum Ethnography (University of Oxford) especially my supervisor Elizabeth Ewart; the Old Fire Station, Oxford; the Imperial War Museum; The Garden Museum; The Museum of English Rural Life and all the people who have engaged with the project either virtually or in person. Thank you for joining me on this enquiry of what it meant to recreate an allotment in the style of 1918. The artist’s journal of poems: Portal: 1918 Allotment detailing the project is now out and available at Blackwell’s Broad Street and online; The Old Fire Station, Oxford; Little Toller Bookshop and The Museum of English Rural Life. We will update the Fig website project page with further documentation, including videos of the talks for those that could not make it, in coming weeks.

This is my last blog post and I wish you all good health and for the growers – a good season ahead.