Journal — February 2022

We are experiencing a mild winter. As a grower, I am missing the cold and the frost. Certain diseases and pests can now thrive all year round, which makes for increasing challenges on the allotment, particularly if one is growing organically. While seeing roses in bloom can lift the spirits on an unseasonably warm valentine’s day, it’s hard not to think about the knock-on effects that out-of-seasonality can have. Various creatures might not have enough food – such as migrating birds that have not arrived on our shores yet.

Growing draws attention to the overall rhythms of life and is quick to show up imbalances. One such imbalance is access to land. I have previously written about what I call ‘The Right to Wellbeing’ or the fact that six rate payers from different households have the right to demand land for allotments from their local council. Not enough people know about this, and so allotment waiting lists continue to grow. At the same time, allotmenteers are also actively losing access to land. I received a sad email from a grower who, along with dozens of others, had been evicted from private allotments which had been cultivated for over 100 years. The land, unsurprisingly, is earmarked for a housing development.

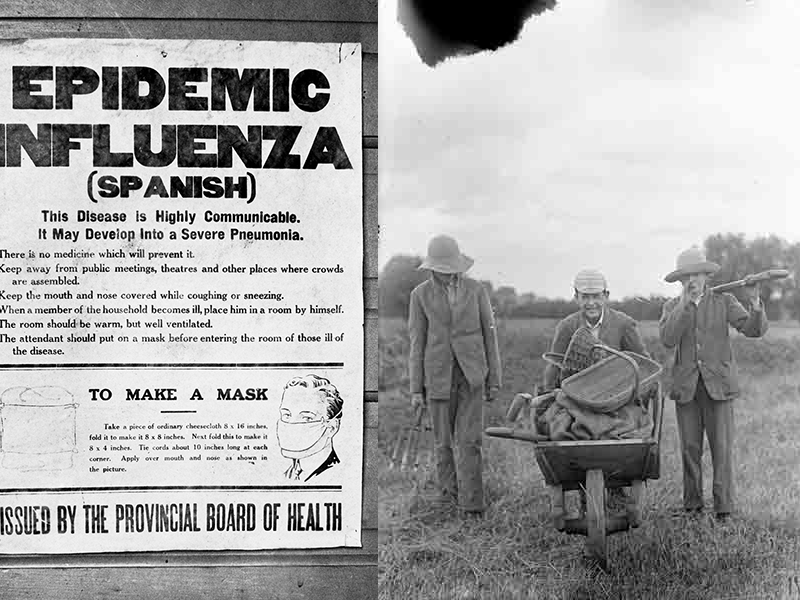

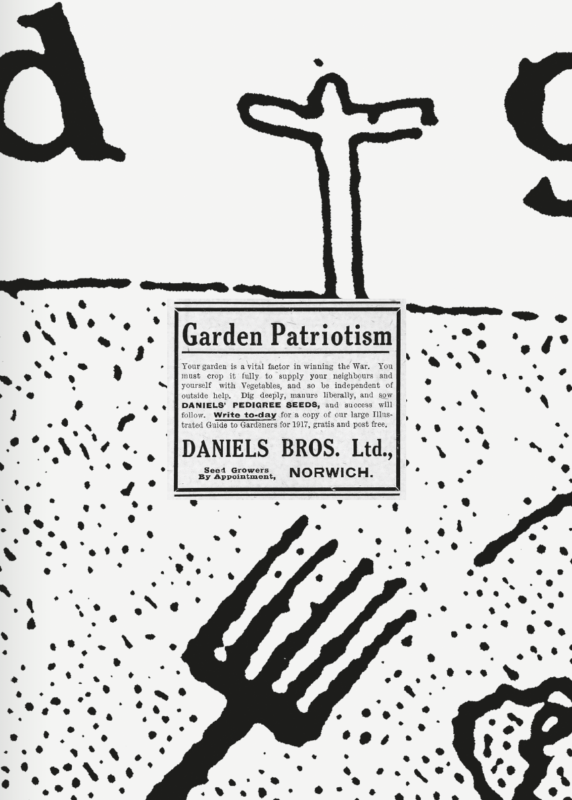

It is of course the case that people need somewhere to live. However, I feel one of the lessons from the ongoing pandemic is the enormous value of outdoor space. As space- efficient buildings go up in urban centres it seems as though the first casualty is the space around the buildings. As well as recreational space, I (not so quietly) worry about the space for growing food. Even as concerns are raised about the distance food must travel to people in cities with the accompanying carbon miles, provision for growing food in cities is reducing. I fail to wrap my head around this stark contradiction.

More than I anticipated, when I talk to people about growing in urban spaces, they immediately reference vertical, rooftop or underground gardens. These are all innovative solutions that should be explored but I still feel that there is something powerful about connecting directly with terra firma. Furthermore, vertical or rooftop gardens tend to be in buildings that are controlled by the occupants. The great gift of allotments (waiting lists notwithstanding) is the possibility to walk past a site that catches your eye and then to end up growing alongside people you would have otherwise never met. Allotments strike a wonderful balance between bringing together diverse groups of people from all walks of life in an unforced way. You only have the conversations you want and yet many sites also offer annual gatherings where people can indeed come together communally.

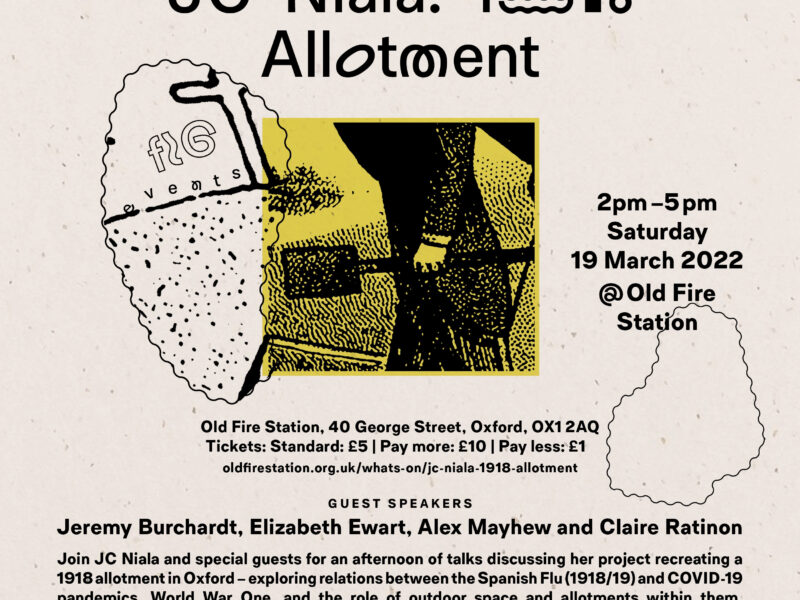

There is also something about continuing to work with the soil of the ancestors. I feel this at the site where the 1918 Allotment is located. On the one hand I am reaching through the soil to touch history, but I also feel that history is reaching back towards me. This is why I felt so acutely the loss described by the allotmenteer who was evicted. His connection with that soil and its previous cultivators spanned a century.

It is also this long view that gives me hope for allotments despite the present challenges. This is not the first time in their histories that allotments have been under pressure. In the 1960s, many across the country fell out of use and would have been lost entirely were it not for the actions of committed growers who kept them going for future generations to come. We can still do that now. Allotments are responding to the imbalances in which work can take over our lives. These days it is possible to get a half, quarter or even an eighth sized plot which allows for a more manageable time commitment than the traditional full plot that is the size of a doubles tennis court. The other interesting thing about allotments is that they make one make time for the things that really matter. Research carried about by Dr Abigail Schoneboom on allotments in Newcastle found that the act of simply having an allotment forces people (in a good way) to down their office work tools and pick up gardening ones instead. Her work made me think about another positive loss. The way one loses oneself when immersed in jobs at the allotment plot. It is a loss of self that allows one to become part of something greater – the nature that sustains us all.