Journal — September 2021

There has been a lot of news about the fact that there are now more women growing on allotment sites than men. In a sense we have come full circle from 1918 when there were lots of women growing on allotment sites across the country while men were fighting in World War One. My own research found that there are more women growing on allotment sites than is often realised as women tend not to leave the same paper trail in the archives as men and also women are more likely to use allotment plots differently. I was fortunate during the course of my research to work from an 80-year-old archive of an allotment site that I cultivated on. What I came to realise is that even in cases where the plot holder was named as a man – women often cultivated on the same plot.

Currently there are many plots across Oxford that women share with their husbands, friends or other relatives but do not appear on any official allotment records. As it happens the same is true for children – some of whom even cultivate their own plots but because of their age are not going to be the official plot holders. It is this difference of use in sharing an allotment plot with others that masks women’s participation. I also found that women are more likely to be flexible in their use – for example, looking after a sick friend’s plot (for even an entire growing season) but never referring to the plot as if it were their own. Many couples who share plots will split the plot with each person cultivating their half to their own tastes. It is of course harder when working with archival materials to find traces of women but it is possible to see from other media that there must have been large numbers of women allotmenteers. The advertisement above courtesy of the Catherine Procter Collection appeared in Punch magazine in early July 1918. It is specifically targeting the women allotmenteers and would not have been taken out unless there was enough of a potential market.

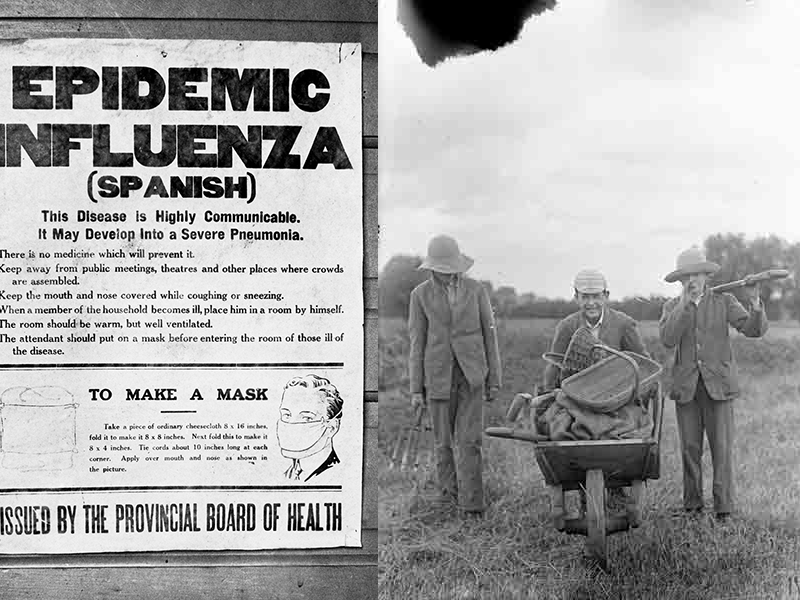

There is another aspect of history in 1918 that is often referred to as ‘hidden’ or ‘forgotten’ and that is the 1918/1919 pandemic. And once again it is women and children’s histories that give important insights. The children’s skipping rhyme

I had a little bird

Its name was Enza

I opened the window

And in-flu-enza

does not belie the horrors of the numbers of people who died as a result. And it was often women’s letters that detailed the challenges that people were facing such as an extract from Welsh Bennett’s wife from the National Archives:

Things here are in a terrible state this new flu as they term it is quite a plague & taking people off as they walk along the streets in fact the undertakers can’t turn the coffins out or bury the people quick enough there’s families of 6 & 7 in one house lay dead its really terrible dear & makes one quite nervous of going out nearly every house along here the doctors are in constant call but thank God so far we have escaped.

We are living in the era of ‘hidden histories’ where story after story is being unearthed that shed light and make us look differently at what we thought we knew. I remain intrigued by all the women (and children) who form a core part of allotment history and whose stories are still held within the soil.