Journal — February 2022

One of the biggest learnings I have had from the 1918 Allotment project is the power of documentation. Gardens warp time. When one has just planted something, it can feel like forever before it comes up – the weeds always seem to come up first. That said, once things get going there are 101 jobs to do and then not enough time to do them in. Long summer days make idyllic allotment evenings. Like those of spontaneous harvest sharing with plot neighbours washed down with fresh cider. I remember an allotmenteer sharing some schnapps he had made from scratch. That included the fruit trees he had planted. The sense of satisfaction he had for a drink that was decades in the making was palpable (and delicious too).

The gentler summer evenings soon give way to the busyness of autumn and harvest time. It may seem counter-intuitive but one of the struggles many contemporary allotmenteers (particularly those who are single or have never had an allotment before) have is what to do with all the food. Potatoes need storing, pickle-making takes over and excess vegetables need preserving to make them last through the winter. Allotments follow a rhythm that is as old as the land but one that can be decidedly out of step with our modern lives. With time that expands and contracts and managing an allotment alongside work, family life and associated joys and pressures – one can lose track of the exquisite moments on the plot.

A great joy of working with Sam (from Fig, the organisation that commissioned me) on the 1918 Allotment has been the poems and blog posts that I have been writing to document the project. While gardening itself can be like a meditation, it does give rise to many thoughts. In the moment of participating with the earth, plants and so on in growing, I can find it hard to speak. It is as though my mind has moved into a place beyond language and other senses are engaged. Yet, gardening infuses language through metaphors and idioms the world over. One of my favourites is a Spanish proverb ‘More grows in the garden than what the gardener sows.’

In my case what also grew (apart from the plants on the allotment) were the words and ideas that Sam encouraged me to put down before I forgot them. The joys of smartphones meant that photographs were added into the documentation as well. By the end of the growing season (including all the visits to the allotments) we found that there was enough material for an artist’s journal of poems comprising poetic, photographic and narrative documentation of the 1918 Allotment project. As is so often the way returning to them through edits of the book, I found that there were many things I had indeed forgotten (or in some cases didn’t even remember writing) and so have now added journaling to my gardening practice.

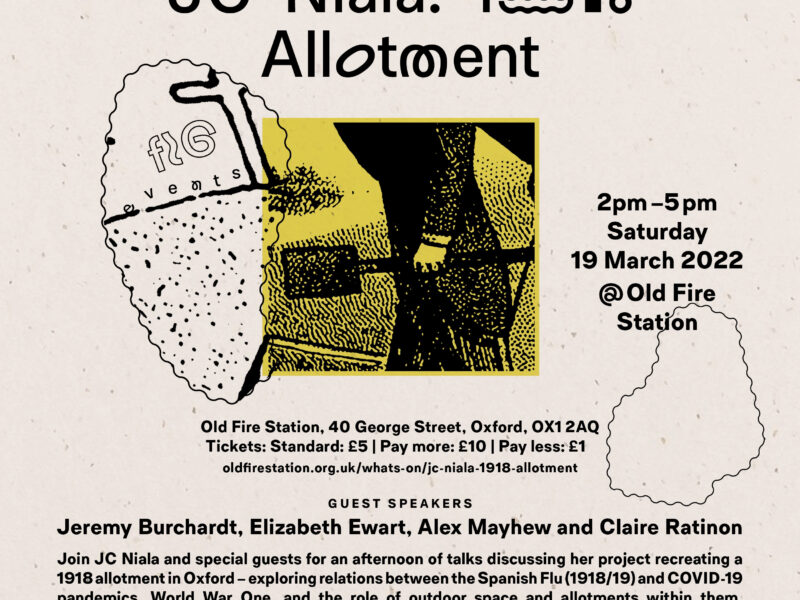

We are launching the book on Saturday 19th March at The Old Fire Station in Oxford and you are very welcome to join us.

Whether you are an active grower or not, I would encourage you to take note of the environment around you. It doesn’t have to be big work – even just a few words such as – ‘warm, wet in the morning, daffodils coming up’, when consistently noted over time can build into a fascinating account of your world. During three years of my doctoral research, I kept a weather diary noting rainfall, humidity, wind, atmospheric pressure, and just one line on my thoughts about the weather that day. I was amazed to find out that my home garden (due to various peculiarities) has its own little micro-climate. I can also confirm (contrary to popular belief) how much less it has been raining in the Southeast of England compared to when I was in my teens. Documenting patterns is not only practically useful, but it also reminds us of the truisms that can get stuck in our imagination of the world around us. So often we make assumptions about our world based on outdated information. Actually taking the time to really observe our environment and note it down brings us more in tune with it – sometimes in the most surprising ways.