Journal — August 2021

From Pigment to Paint

As the year progresses I am building up a small collection of locally sourced colours – the beginnings of a vernacular palette. To make useable paint from these various colours calls for the addition of curdled milk. An old technique, which exploits the protein in the milk as a binder and base. There being no cows immediately in the vicinity to supply it, I go with the vernacular of the local Sainsbury’s and follow an old manual’s recipe with UHT soy milk instead. To my surprise it seems to work. I get to wondering whether this could be a goer for a locally grown paint, and plant a row of soy beans on the Elder Stubbs site. They seem to grow bright and strong. How much milk they might yield, we’ll have to wait and see.

In order to make milk paint weatherproof, the old recipes also call for hydrated lime. Like all lime-based products, this comes from limestone – the ubiquitous OX4 material, which yielded so many of Dr Plot’s fossils. Death-in-life, an ambiguous substance at once biological and geological, made of crushed bodies in their countless millions. It forms the hills all around here and much of the architecture too – especially the many crumbling stone walls of Cowley, out of which liberated shell fragments tumble in cascades of dust as the stones erode. I often stand peering into these crumbling walls, trying to make out individuals. I wonder what hopes, fears, appetites these creatures felt? What would they make of their present state, compressed into layers, become a ‘material’?

Oxford Limestone

Whatever the agency of limestone may be, it is surely a good candidate for inclusion in my vernacular collection. Or so I thought. The city limits are pockmarked with old quarries where the stuff was extracted for generations. The Hollow Way nearby got its name from the scouring action of so many limestone blocks, dragged on their journey from Headington quarries to the river. But limestone as part of a viable vernacular today? More doubtful. The old quarries are now housing estates or nature reserves, supporting rare flora. Full cycle: life-in-death.

I set out to source some limestone from nearby, and in what has become a recurring theme, find out just how difficult this is. A local heritage lime specialist advises me that nothing is now quarried in the area. Starting with local dealers I get on the phone, learning about the companies they source their lime products from. I’m directed to the websites of international mining corporations, some of whom have quarries in the UK, some of whom don’t. At last I find myself on the phone to a quarry in Derbyshire. They do still extract limestone, but for the hydrated (treated) stuff I need, they buy it in from another company. I speak to them. They, too, quarry in Derbyshire. I do then find details of a quarry on the border of the Cotswolds. I email them. Yes, they sell oolitic limestone dust (unprocessed). By this time, my 5litre tub of hydrated lime from Ebay has arrived.

So, perhaps no longer as vernacular as it seems. Like all quarried material limestone is finite, as Oxford architects learnt to their cost when the good stuff ran out many years ago, and a run of badly weathered buildings preceded the abandonment of the local quarries. What place this ghost material, still so abundant underfoot? Perhaps an honoured ancestor, a companion to be cared for rather than used? As Eames Demetrios (grandson of Charles & Ray) points out, to be really ‘vernacular’ a form must embody, more or less unconsciously, the prevailing values and imperatives of the day. Any attempt to resuscitate past forms and adapt them to today’s changed circumstances is likely to fail, both functionally and probably aesthetically too. The real vernacular style of today emerges from the economic imperatives giving rise to such things as shrinking chocolate bars and paperless statements. These imperatives, Eames contends, have shaped more objects than all conscious work by designers put together [1]. (The ‘invisible hand’ turned craftsman, calloused fingers creepily sculpting all things while artists look on?)

Oxford Yellow

Limestone may not be a goer, but there is another local paint-making stone I want to investigate. It’s immortalised at the local shopping centre, whose concrete relief mural shows an Oxfordshire farm wagon, painted the traditional yellow. (The mural was commissioned, inevitably, to adorn a building whose construction required the demolition of the entire farming village it commemorates.) This yellow, so-called Oxford ochre, was quarried nearby and according to Robert Plot was “accounted the best in its kind in the World” [2]. In fact it isn’t the garish bright yellow claimed in the mural, but the much subtler shade which seems to have been irresistible to humans from time immemorial. Plot described is as being “of a Yellow Colour and very Weighty, much used by Painters simply of it self, and as often mix’d with the rest of their colours”. As local musician Rawz remarked to me: we think of Oxford’s official colour as blue, whereas really it should be yellow ochre.

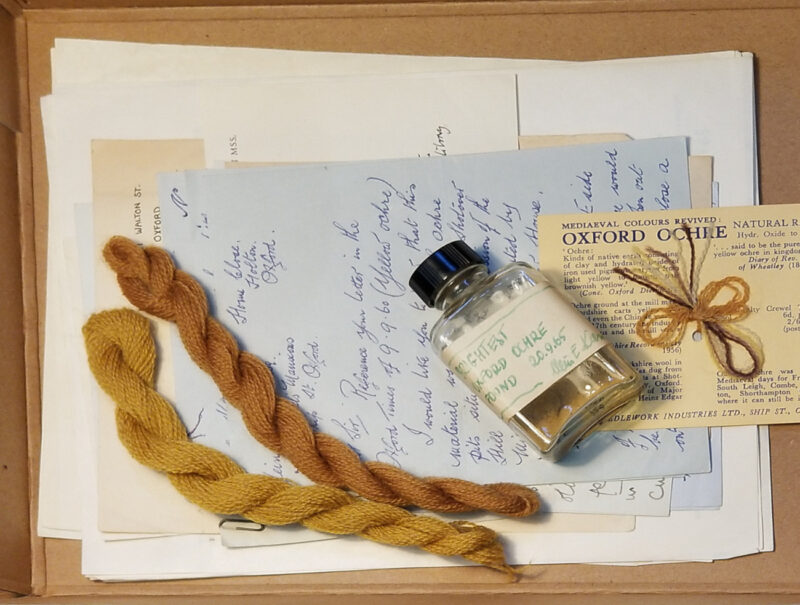

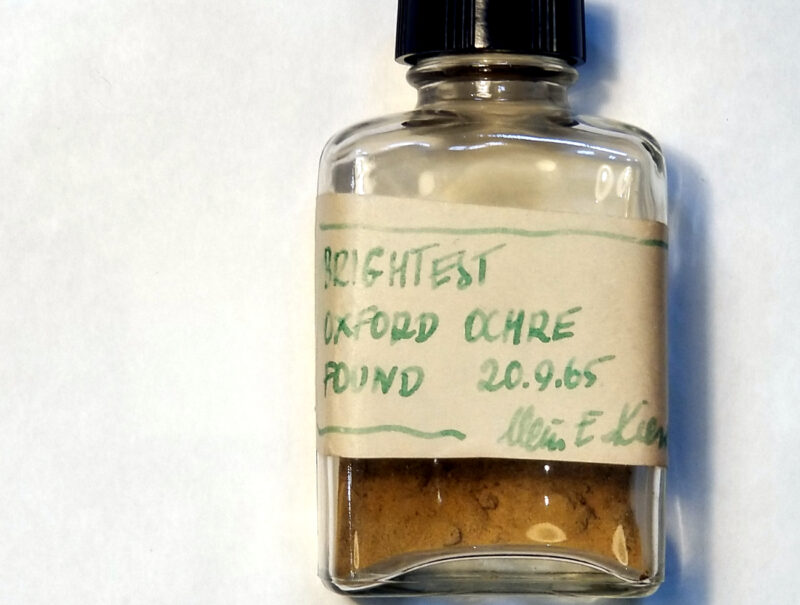

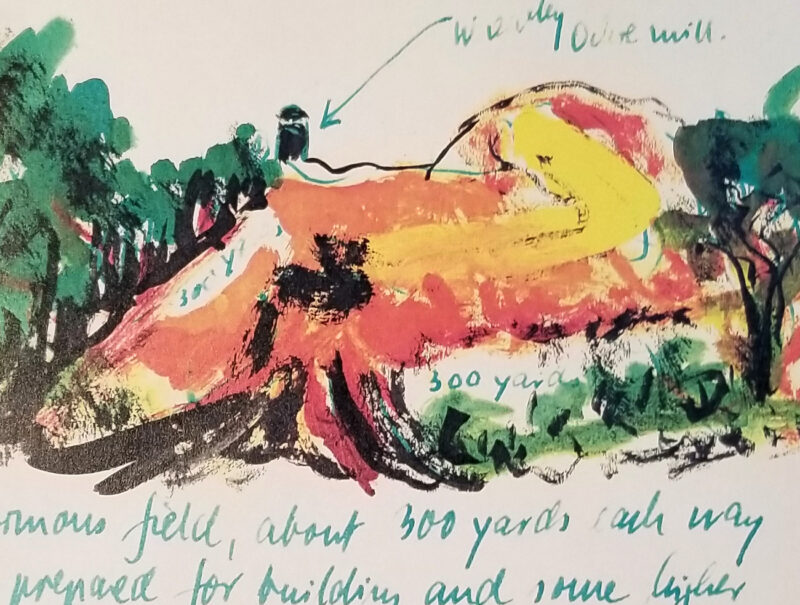

Today Oxford ochre is a nostalgic memory only. Like limestone, ochre is a geological blessing, occurring as seams of iron-rich earth in amongst the Whitchurch Sands which crop out on various hills nearby. All that remains of the local ochre industry now are overgrown crevices, small fragments scattered about, and tantalising traces in the archives. I become fascinated by the pull this elusive material seems to exert on the imagination. In the local archive I search out a box of material relating to the Oxford ochre. It proves to be a virtual shrine to this lost material; a personal collection of searching and longing for something which had already long gone when its author – local tapestry merchant, textile historian and Jewish refugee Heinz Edgar Kiewe – undertook research in the 1960s [3]. A sheaf of letters records correspondence in which fellow seekers swap hearsay and hand-drawn treasure maps pointing to the old ochre pits. One particularly poignant letter, sent to the Oxford Mail, urges readers to take a rare chance to see a great swathe of ochre being exposed that week on a nearby hill, as diggers prepared the ground for a new housing estate which would cover it forever. Kiewe helpfully illustrated the letter with a view of the site – coloured with a synthetic modern “ochre” paint.

In medieval times ochre was widely used in mural painting, and Kiewe’s archive contains a map of Oxfordshire on which he plotted all the churches where it was used. I set off in his footsteps, and go to visit one of these in South Leigh. I’m keen to see what design constraints this vernacular material imposed upon artists, and if these might be visible in the finished works. Indeed, they are. After a long and tiring walk I arrive in the village, and find a man tidying up as I enter the church. (In preparation, he later tells me, for tomorrow’s bell ringing competition.) He is delighted to show me the wall paintings and turns on the lights, so that the space blazes like an enchanted grotto. The artists clearly adapted their motifs in accordance with cheaply available colours, making use of the strong contrast available between burnt red ochre and white (lime?), with uncooked yellow serving as an intermediate shade in more complex designs. Zig-zag foliage and red stars on white ground predominate, showing the colours at their best.

It’s not hard to be seduced by this earthy material, which seems so ready to solve the artistic dilemma of too much choice. Mr. Kiewe even produced a painstaking reproduction of the colour from his research, for use in needlework: samples of both the raw yellow and burnt red shades are included in the archive as thread shade cards. What materials were actually used to produce these colours, or where they were sourced, I have no idea. Kiewe’s personal project foreshadowed several more recent ones by various paint companies to reproduce and sell “Oxford ochre” shades. Here again we have a dead vernacular re-appearing in self-conscious afterlife as nostalgic throwback. Rather appropriate for a colour which has so long been associated with death and burial; a colour which perhaps gained this association from its ability to survive and grow in strength through fire (from yellow to red), thus symbolising immortal life [4]. Sadly though, the material itself isn’t forever – its local pits were commercially exhausted some time around the 1920s [5].

I have all but given up on Oxford yellow when a friend invites me to come and have a look at some clay she’s turned up whilst digging foundations for a new building, in a back garden just uphill from Elder Stubbs. I arrive to find a great pile of it and gratefully fill up all the bags I can carry, thinking I might use it for making tiles or glazes. But it is immediately clear that here in Church Cowley, halfway between the marsh and the true clay outcrops further east, the clay is shot through with seams of sandy impurities. In places, pure nuggets of rich orangey yellow show up. The clay has dried hard in the summer sun, enabling me to pick through chunks of it with a knife and scrape out the tiny bits of yellow. After 30 minutes I have a small teaspoon of reasonably pure dust. Mixed with a little water and brushed onto paper, it is indistinguishable from the tests I’ve made before with my piece of Shotover ochre. I start calling it Okay Ochre and carefully tip the remainder into an old spice jar. To me, Okay Ochre will always smell of cinnamon.

So, Oxford yellow lives on. Okay Ochre, being found in surface deposits, does seem an appropriate candidate for inclusion in my collection. Not only does it link to the past, but fits Eames’ notion of the neoliberal vernacular, speaking as it does to the skyrocketing house prices in East Oxford; prices which compel those who can afford it to maximise space and value by digging ever more foundations for extensions, garden offices, and the like. One place this isn’t happening (for the moment) is Elder Stubbs. And land devoted to plant life has a huge advantage over foundation trenches, pits and quarries. While ochre dug from the ground may hint at eternal life, living beings grown from seed can actually fulfil this promise.

If Oxford yellow – if any colour – is to remain abundant into the future, it will be of a different kind: a kind which /can/ be replenished, through the forces of life itself. With this aim in mind, the next plant I put onto the allotment is Coreopsis Tinctoria. Its name is a clue to its long use by dyers, producing yellow-orange flowers which might just yield a dye to rival the exhausted yellow earth. It may not be light-resistant. The artworks made from it are unlikely to be intact, as ochre paintings are, thousands of years from now. But notions of immortality perhaps need to change. The compulsion to create everlasting artefacts is the same one which has put the future of life on earth into doubt, just like Cowley’s concrete mural destroyed the place it celebrates. So as South Leigh’s painters invented motifs to suit their burnt reds and lime wash, it may be time for artists to bend again to our materials. This time, the forms and motifs called for will need to find ways of accepting materials’ biological inclinations. In other words, their (apparent) impermanence – which contains nonetheless the seeds of eternal life.

[1] Eames Demetrios (2015), ‘What might Modern Folk and Vernacular Design be?’.

[2] Robert Plot (1677), ‘The Natural History of Oxford-Shire’.

[3] Heinz Edgar Kiewe (1955-63), Collection of items relating to Wheatley ochre, Oxfordshire History Centre.

[4] Onya MacCausland (2017), ‘Turning Landscape into Colour’.

[5] Patrick Baty (2011), ‘Oxford Ochre’.