Journal — July 2021

A Natural History of Oxford-shire

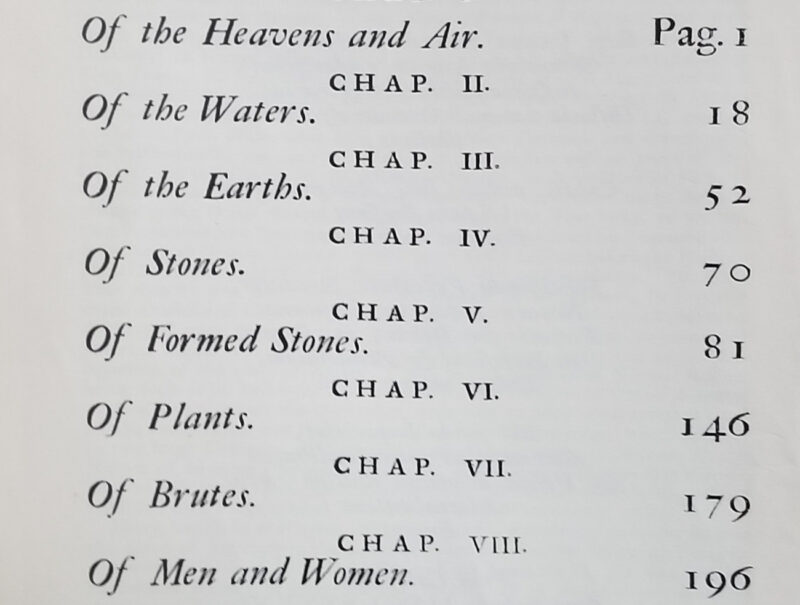

In the 1670s Robert Plot, Oxford chemistry professor and naturalist, set out on a series of excursions around the Oxfordshire countryside. Through friendly chats with landowners, recording of local legends, and direct observation he compiled a great scientific survey – with plenty of open-minded speculation and folklore thrown in. This mighty tome, ‘The Natural History of Oxford-shire’, covered everything from the local air, water, earths and stones up to plants, animals, people and finally arts. It is a model of holistic learning from the early days of natural philosophy, in which Plot’s disarming ‘beginners mind’ invites us to look closely at the land around us and learn all we can.

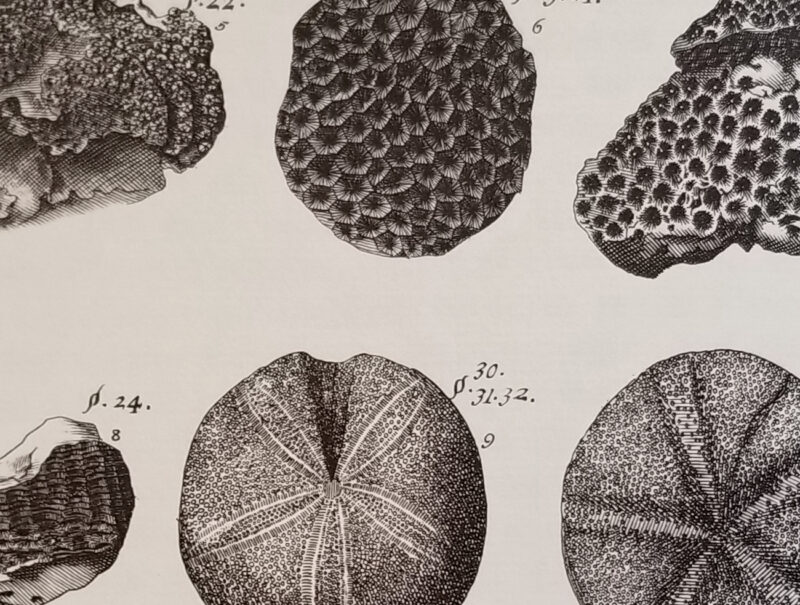

As I set out on my journey to understand the land around Elder Stubbs, arguably an alienated and ignorant urbanite, Plot’s work suggests a useful approach. He was writing at the dawn of science when much was provisional and great swaths of the world were a mystery. Today when much knowledge has been lost and the local neighbourhood can feel far away, such humility in the face of the unknown seems a good place to start. Plot treats all he finds with equal curiosity and seriousness, from speculating on the nature of shell-like stones (known today as prehistoric fossils), to legends attending ancient monuments, to anecdotes about local people said to have returned from the dead. And why not, when what might seem irrelevant today could turn out to be the material of tomorrow’s new theory? In this spirit I will set off on my own wanderings, and speak to those I can, to get a sense of this landscape and (building up from there, as Plot showed) the vernacular materials it might support.

Looking for Clay

What better place to start than looking for clay? Natural, abundant, a well known healer of the souls who work it. Like Plot I set out to find where it might be, and if I might forage some for artistic use. Instead of wealthy landowners I turn to Youtube for advice, where fellow seekers share the results of their own quests for reconnection with the land. Without the benefit of local clay pits or living wisdom, we scrabble about uncertainly. One man advises to look near streams. He demonstrates, bending over and poking at the inscrutable ground. At last a caption admits, “it’s random – so here’s nothing”. And on he goes to another spot.[2] What is this performative digging all about? The showing of hands, dirtied in authentic soil, via smartphone and internet? Clearly the need here is not actually for material – the world has more than enough pots, surely. Rather we are itching at another need, newer or perhaps older. A need to make meaning from the earth, to belong to it, to be situated somewhere real.

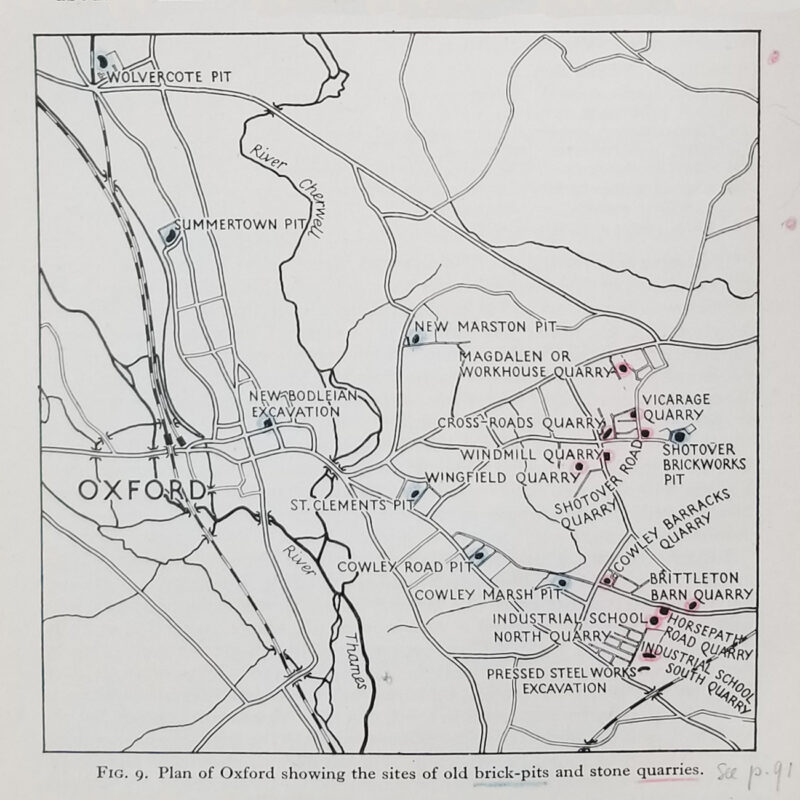

In Cowley the clay is a little easier to find. Down here on the Marsh we are near to the Oxford Clay and old brickpits. One of them used to be under Tesco carpark where building works are going on at the moment. I pass the hardhatted builders on their fag break, thought of asking if I could peer down their big hole. But, feeling shy, I say nothing. Instead I turn Eastwards to the higher slopes, less covered by tarmac and so accessible to the silent wanderer. Like a raised eyebrow all round the allotment, on the brow of the Cowley slopes the Kimmeridge clay is exposed. Ancient potteries are dotted about, following the line of the hills. I find that there were distinctive types made here in Roman times – designs unique to Cowley. In the History Centre I stare at reproduced drawings of these incised dots, swirls and animals. Fascinating cosmopolitan, classical motifs – yet tailored to and supported by this most humble of local materials.[4]

![Ceramic makers marks from Blackbird Leys (1) and Cowley (2-12). [4]](https://fig.studio/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/young1977-cowleyMakersMarks1300px-800x605.jpg)

![Decoration of Roman vessels made in East Oxford. [4]](https://fig.studio/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/young1977cowleyDecoration1300px-800x605.jpg)

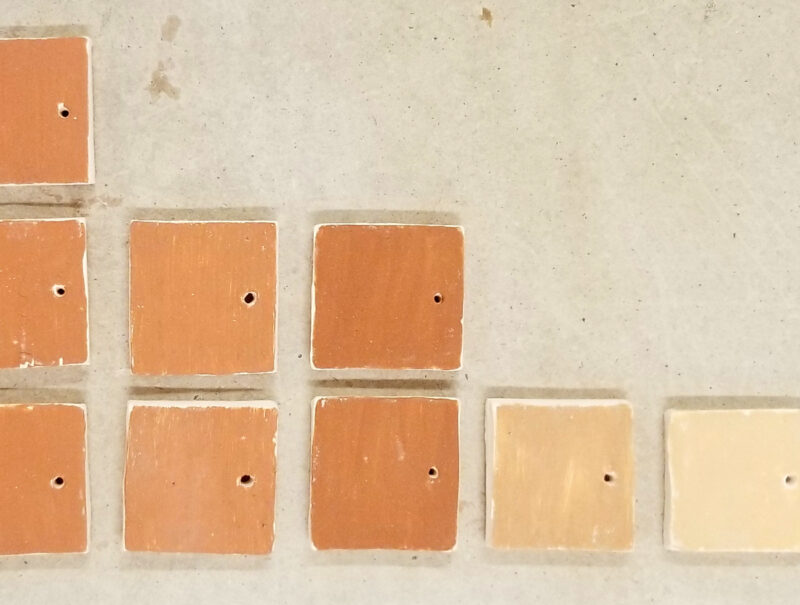

The clay in each area is unique. On the brow of the hill it is thick as cheese, and brown-grey. A drainage ditch gouged smooth by great blades shows the farmer’s battle with it. Further down on the banks of our stream it flashes white, soft as cream, layered next to hard shaly-blue. I learn from internet videos how to wash it, pour off the good stuff, and strain through a pillowcase. The blue shaly stuff is terrifying and mysterious in its raw form. Raffa, keeper of the kiln, eyes it suspiciously. I smudge a fingerful onto tile and he humours me, puts it in. It fires to the colour of soft blushing flesh. Then he smiles and shows me inside a huge tub he’s been keeping round the back – full of white clay soft and wet as whipped cream. He says he got it from the bottom of a Cowley well, but won’t tell more.

Soon people start to bring me bags of earth with stories in them. The nursery staff in Florence Park have just dug out a pit, and give me a bag of uncertain material. (Bordering Elder Stubbs, their place used to be farmed in strip fields – you can still see the humps and hollows, especially when the park floods in winter.) I wash and strain the orangey lumps – sure enough there is clay in here somehwere, though mixed with lots of sand and what must be alluvial detritus. I paint it onto a tile and it fires a beautiful yellow-brown, but the pot I make from it crumbles to sandy pieces.

I marvel at the range of colours given to me by the nearby earth. But as my collection of test tiles grows, so does my unease. Clay may be abundant, but there is only one way to get it, and that is to dig holes in the ground. Later I learn of the fragile ecosystems reliant on the Boundary Brook banks, which are drying out from deep gouging and must urgently be preserved and re-wetted to save the peat they enclose. Never again will I take clay from here.

So what to do with the small, precious lumps left from my foraging? I had initially planned to make tiles from them, as ingredients for a decorated architecture rooted in vernacular material. Now I realise such quantities of clay can only be obtained by the digging of great pits – suitable use for builders’ spoil heaps perhaps, but hardly something to initiate in the fragile landscape nearby to our plot. So instead of making objects with my samples I brush them thinly, onto tiles made of clay brought down from Stoke on Trent. I guess digging big holes is still ok there. The glazes come out beautiful; a subtle spectrum of vivid orange to purpley red.

Emboldened by these experiments, I try to make the process more local still and attempt a pit firing, using scrap wood and old cuttings from local trees. On the brow of the hill overlooking the allotment I dig a couple of feet down, and I reach bright yellow sand. The tropical shallows, I assume, of our prehistoric sea. The only fossils I find are the cut bones of Victorian dinner parties. I pile all my scrap wood in, and after letting the almighty blaze smoulder down overnight, I scrape and poke in the ashes looking for my little tiles. Most of them have exploded. But they are beautiful, pinkish reds and blacks.

These humble tiles, once fired, will now exist for thousands of years. All considered, I’m not sure if this practice is ecologically sound – though it’s as locally sourced as it gets. I think of my asthmatic friend nearby, bemoaning the wood-burning hipsters filling our postcode with particulates. Like my Youtube tutors, I feel sated by my ritual of reconnection with the earth – hair and clothes scented with fire smoke. But to what end, I’m not sure. Perhaps the process itself is all I wanted. Perhaps, once formed, these tiles should be laid back into the ground slippery and unfired. I’m reminded of pots at prehistoric sites deposited like this – only half-fired, never to be used, left and buried (an offering?) in the pit where they were made.

I return to the pit a week later, having forgotten about it. The rain has now washed the soot from the sides, and I see something lovely. The heat of the fire has baked the yellow sand to a bright red-orange. I scrape a little off with a knife, grind it, and make a mark.

[1] Robert Plot (1677), ‘The Natural History of Oxford-Shire’.

[2] Rakrido Videos (2020), ‘How to Find Clay’.

[3] W.J. Arkell (1947), ‘The Geology of Oxford’.

[4] C.J. Young (1977), ‘The Roman Pottery Industry of the Oxford Region’.