Journal — July 2021

"As is so often the case, nature did her thing, and I played a reasonable second fiddle."

The 1918 Allotment had her first visitors this week. It was a glorious summer’s day – if a little hot (I am whispering this as the English sun doesn’t need much encouragement to hide away if he feels that he is being told off for over-exuberance) and I was unexpectedly nervous. It is one thing to work away at a project and muse on it through journal posts but quite another for people to actually arrive and engage with it. I was also nervous about reading the poetry I have been writing as part of this project – I had not shared my poetry aloud in years!

As is so often the case, nature did her thing, and I played a reasonable second fiddle. I am under no illusion that our guests could have simply spent time on the plot without my uttering a single word and would still have had a magical time.

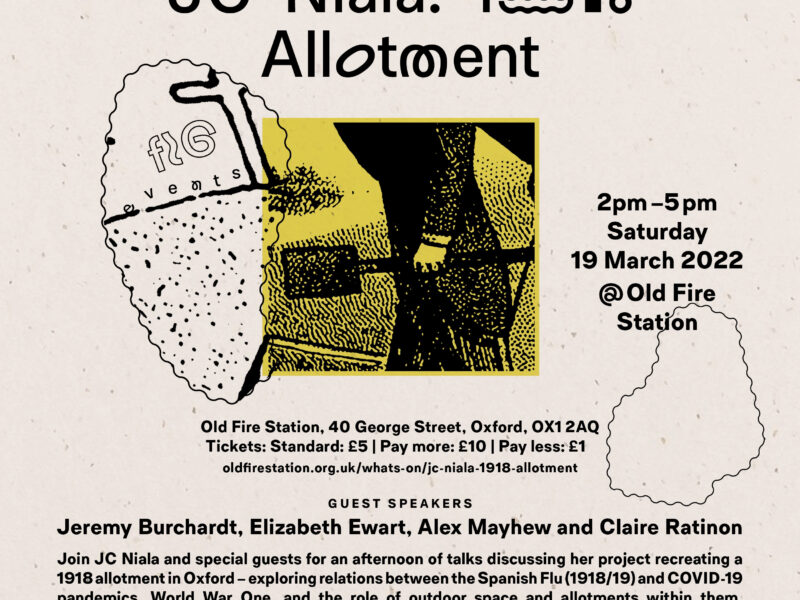

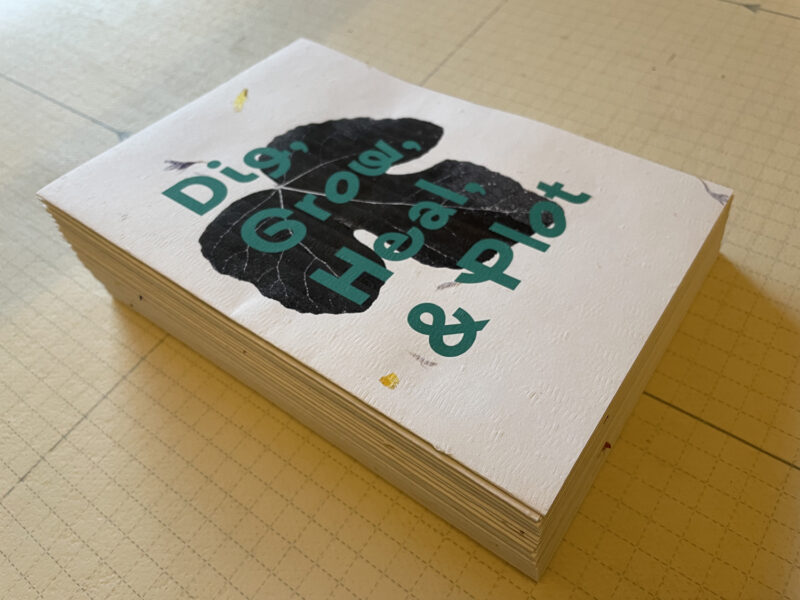

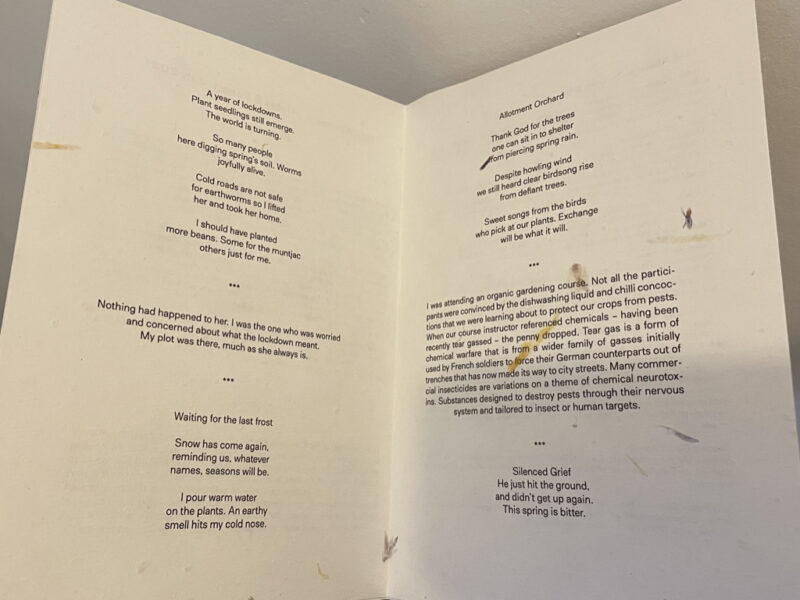

Sam – my brilliant collaborator and founder of Fig the project that hosts the 1918 Allotment – had produced some beautiful leaflets with my poems, a map of the plot and some information about the plants that are growing on it. He was also kindly co-host on the day.

It struck me as I stood outside the allotment gates with the first group of visitors (we hosted two different groups back-to-back on one day) how relatively few people in Britain have had the opportunity to visit an allotment site. Mainly for security reasons, most allotment sites are fenced and have lockable gates. It was not long before one of our guests brought up the irony of a democratic and equitable allotment site that also locked out most of the city that surrounds it.

This led to a discussion about the various enclosures acts and the ripple effect of land having become a commodity. It is easy to lament the loss of common lands but much harder (now that we have the systems that we do) to convince people who own any patch of land, however small, that it would be better for us all to have access over and above individual rights. There is also the effort and labour that one puts into the land that does (all puns intended) cultivate a sense of ownership.

As part of my doctoral research, I interviewed an ex-allotmenteer who grew on an unfenced site that he had initially been attracted to by the lack of obvious boundary. He said that walking onto the site unimpeded by fumbling for keys had given him an enormous sense of freedom and transported him (in his imagination) to a time when there was ‘more common good’. This delicious sense rapidly came to an end when, three seasons in a row, his entire harvest was stolen – just before he could get to it. I told him I admired his tenacity to keep growing after the first time it happened and he admitted that he is far more interested in the growing process than he is in the food he produces. He only left the site because he felt that he was ‘being made a mug’. His story stayed with me because it spoke to all the different stages of growing from which it is possible to get pleasure. This range of experiences is also what we wanted to offer our guests on their visit. Some harvested potatoes, others sowed seedlings, and yet more popped fresh peas into their mouths that exploded into sweet tasting memories.

My nerves dissipated as the living memorial (that is the 1918 Allotment) delivered what I hoped it would – triggering different forms of remembrance through engaging with it. Another form of participation was through the food and drink that we served. I had made jam from the strawberry patch on the site, and although by now all the strawberries had been picked, the taste allowed visitors to travel back in time to the fresh ripe strawberries. Also on offer (entirely optional) was World War One rum. Given to soldiers up to three times a day, rum was drunk neat or in coffee, tea or cocoa – both in 1918 and now at the site. Those who partook spoke of the change their senses went through, and of what it must have been like to be egged on, by way of a hard spirit, to enter into battle.

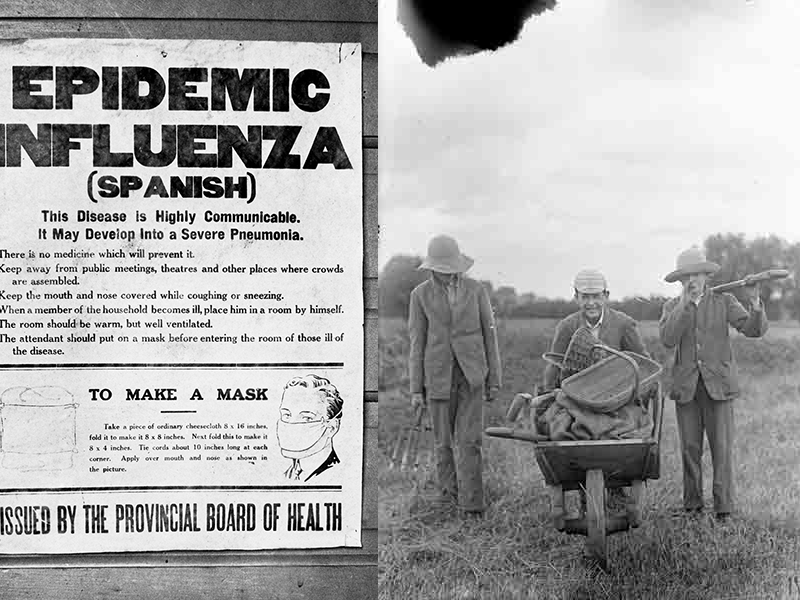

Even though as they say, a good time was had by all, I was thoroughly exhausted at the end of the day and slept 12 hours straight. It had been the first time since the current pandemic began that I had spent any length of time with more than a handful of people. When I woke up, I thought even more deeply about those who had fought in the Great War, only to return home and have to fight for their lives all over again during the ongoing 1918-1919 pandemic. It felt appropriate to have been remembering them as we return to the world.