Journal — July 2021

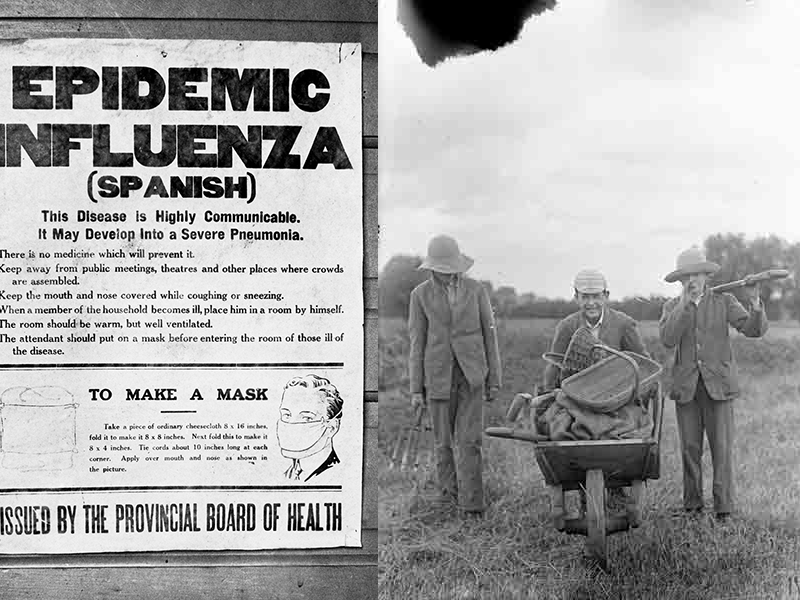

The current pandemic has been a stark reminder of the importance of health. It has also magnified health inequalities. What is devastating is that on the surface of it, many of the things that are health sustaining seem straightforward to achieve. One of the simplest things being simply going outside. Sadly, not all outsides are created equal, and the best outside is somewhere that has direct access to nature (which usually means that there is also likely to be less air pollution). Both in 1918 and 101 years later when the current pandemic started, not everyone had or has access. To be blunt – those who are financially wealthier have more access to nature than those who are financially poorer.

As I discussed in my last blog post, the stereotype of allotmenteers is that they are working class. There is some truth to this – early allotments were started by wealthy landowners, churches, charitable people/ organisations and social improvers with the expressed intention of providing labourers with the possibility of feeding themselves. (It is, however, always worth remembering that these were often the same labourers who saw their access to land forcibly taken away through land enclosures enacted by the political elites). While in rural areas land enclosures are credited with increasing agricultural productivity, it should also be remembered that allotment plots were, and still are, leased from landowners of different kinds. Early allotment rents were ‘competitive’ – in this context meaning that people had to have some money to begin with in order to be able lease a plot.

In urban areas this meant that from around the time of World War One, allotment sites had people of all social classes cultivating on them. This can be seen depicted on allotment postcards of the era such as this one on the Garden Museum website. What makes the difference is the relative consistency with which people of different backgrounds have carried on allotmenteering in the intervening century. Those who managed to secure their own home gardens were more likely to retreat to cultivate in them. In the present day, it is still the case that one in eight households in Britain has no garden. Throughout the last century there have been those who have campaigned for the right to wellbeing through access to nature for everyone. More recently there have been attempts such as the proposed Nature and Wellbeing Act spearheaded by the Wildlife Trust.

The first wealth is health — Ralph Waldo Emerson

Historically, when it comes to allotments, it turns out that it was enfranchisement (or the right to vote) that was a critical factor in widening access for would-be allotmenteers. Until 1918, you were only able to demand allotment provision in a city if you had political franchise. In order to do so, you had to be a male property owner or you had to be paying at least £10 a year in rent. This ruled out all women and 40 percent of men. Following World War One and after the pivotal year of 1918 – all men 21 and older and women 30 and older were eligible to vote. As well as political enfranchisement – this brought along access to land in urban areas. As long as six people who were registered to vote, and from different households, felt there was unsuitable allotment provision in their area – they could ‘demand’ (that is the legal term) for an allotment site to be created by the council.

I find this demand fascinating because it provides access to many things – land to grow on, nature, Vitamin D, relaxation, exercise, the list goes on – in brief it is demanding the right to wellbeing. What is even more astonishing is that this basic right has not changed in a century. It is still in force today and I have met people who have been successful with their ‘demand’ and established allotment sites that have been developed to the benefit of all within cities.

It is this idea of shared benefit that is one of the reasons that I am happy that the 1918 allotment is on a site with an ethos centred around the spreading of wealth by wellbeing. Elder Stubbs allotment site, where I am developing the 1918 allotment, has been in its current location since around the time of World War One. As I work with the soil, I often think that it holds within it a memory of the period of time I am researching. It is a charity allotment and hosts on the site two organisations – Restore which works for mental health and The Porch that provides support for the homeless and vulnerably housed.

When recently making jam with strawberries from the 1918 allotment, I thought a lot about the word demand with regards to getting an allotment site started. It gave me pause to realise that there is a law that exists that not enough people know about – that gives everyone the possibility to demand the right to access to wellbeing. I hope that more people do decide to take up this right and – if you are reading this – that you will come and visit the 1918 allotment so you can try some of the jam. In the next post – I’ll be sharing how you can arrange a visit.