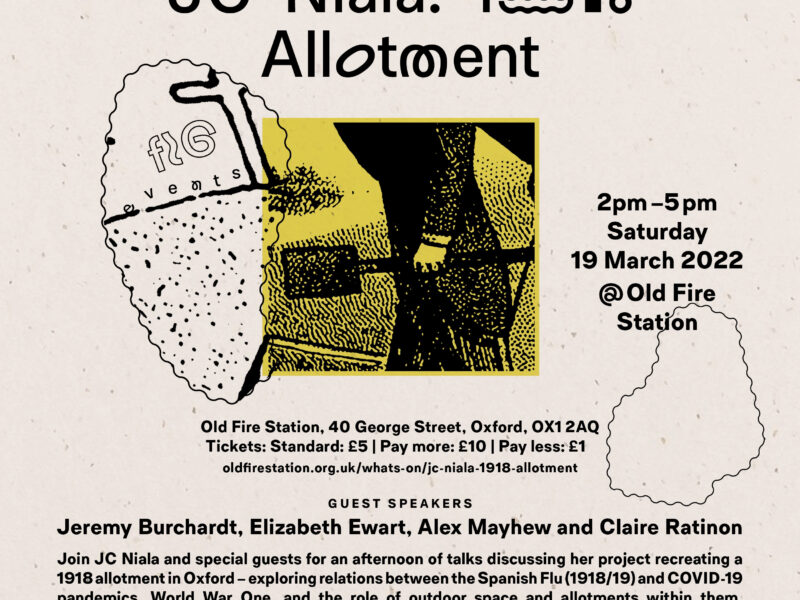

Journal — October 2021

In my search to understand the land around Elder Stubbs, I began up on the surrounding hills: clay, limestone, and ochre. From the mineral-rich hills around Elder Stubbs I lower my gaze to the slopes which come to rest in the marsh, on which the allotment sits. Where limestone passes into the lower clay layers, a spring line forms. This ancient magic is usually hidden in vegetable obscurity from city dwellers, but not always. I was once lucky enough to look around a house which had been built halfway up one of these slopes. When I peered down into its Victorian cellar, as in some Jungian vision I found I couldn’t descend because the wooden stair leading down gave way to rot after the top step. Below, water gurgled up through the floor, filling the room. Whenever I pass that house, I look to the pavement: you can still sometimes see the spring bubbling up through tarmac, despite Thames Water’s frequent ministrations.

This spring, like most of its kind nearby, drains eventually into the Boundary Brook which bisects Elder Stubbs. In fact the allotments would probably not be here were it not for the course of this brook – now straightened, but formerly wandering through what was uninhabitable marsh. A look at old maps explains the odd meandering dribble snaking through Florence Park, as the original course of a waterway which once cradled Elder Stubbs in the crook of its arm, before the dead-straight shortcut we know today was cut through the middle.

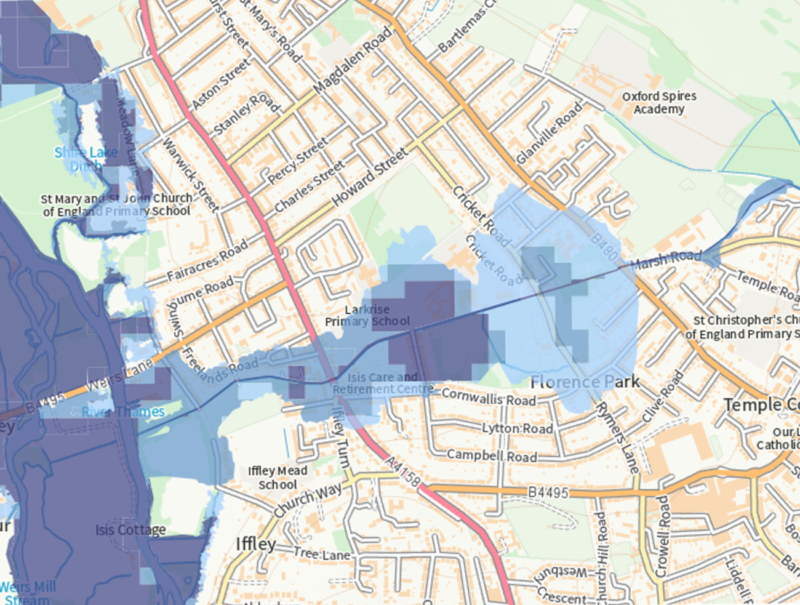

This whole area remains beholden to water. Boundary Brook can easily be spotted on flood risk maps as the finger of danger running up from the Thames along its course. Florence Park not long ago became inundated with groundwater during winter floods, with only the high middles of medieval strip fields sitting proud of the surface. The Environment Agency estimates that Elder Stubbs is at medium risk of flooding each year [1].

After a serious knee injury earlier this year, I took to walking the route of the Boundary Brook as part of my rehab. The distance from Elder Stubbs to its source, or mouth, and back again was until recently the limit of my walking range. Downstream, the brook is jostled between concrete banks until emerging into the Thames through a rather elegant, Brutalist funnel.

Upstream, it’s culverted under the road whose meeting of names (Oxford Road/Cowley Road) marks its course, even over tarmac. Along the foot of the slope, where locals used to cut peat and water still pools under the Marsh Park willows in winter. Huge and happy, these willows – with alder – soak their feet in the watery ground, red roots flashing under the brook’s surface. Uphill, the brook snakes round old hazel coppices giving way to oak wood, until on the far side of Bullingdon Common (now the golf course), it passes upward into an altogether more otherworldly zone. Amongst a corridor of tightly huddled trees it splits in two – or rather, its two sources merge. To the west, it flows from a long-hidden spring somewhere under the Hungry Horse. To the right, the land opens into an eerie valley where ground gives way to wet peat hidden below reeds, and iron oxide springs stain the pooling water. You don’t have to understand the ecology to sense you are entering a sacred, liminal place. This eerie valley, where the brow of limestone acts as an aquifer gently releasing springs down into a waiting saucer of ancient peat, soaks up vast quantities of water. This magical place is protected by the only incantations left to us these days – designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest – and tended by a loving team of devotees.[2]

Artificial pools, dams and barriers are installed in an effort to slow the unnaturally large quantities of water which now gush through, as more and more drains are plumbed in upstream, more ground is paved over, and more rain falls due to climate change. The wet peat holds back the worst flooding from Elder Stubbs and all the houses on the marsh. We have the sphagnum moss to thank for this spongelike effect – a material so absorbent, it was used for bandages during the wars. Today the moss staunches the leaky wounds of sick architecture, with increasingly intense runoff gouging out the brook’s sides. This threatens to expose the ancient peat to air, drying it out and releasing its deadly store of carbon.

When I go to volunteer, I learn a little of the unending labour and movement of material required to maintain the fragile equilibrium of this place. Far from benign, many wild species here are referred to as ‘thugs’ and regularly cut back to give others a chance to flourish. Reeds and sedge are kept in check with scythes and piled up to protect the eroding banks of the brook. The Himalayan Balsam stands taller than a human, filling the air with its sickly sweet scent. This pink-flowered giant is that most modern of plants, having come from elsewhere and so considered an invasive pest, but also – arguably – a comfortably settled vernacular species. It is pulled up by the roots completely, before its explosive seeds ripen. Meanwhile, humans have eradicated all the great ruminant species which would once have kept this fen clear of large plants. In their scything and clearing, conservation volunteers take on the role of ersatz mammoths, giving the littler plants a chance.

Further downstream, the Boundary Brook nature reserve gives a glimpse of how Elder Stubbs may have looked before the marsh was drained, with new ponds cut through the clay.[3] Here, too, diversity is encouraged by vigourous cutting-back of the more strident species. I spend some time there grappling with upstart Blackthorn, which has clearly met my kind before and knows that flesh is no match for its spines (although its understanding of metal tools lags some years behind). The thistles too have their own agenda, merrily using my clothes as transport for their seeds even as I pull them out. In the centre of a great tangle of brambles, I pause my ruthless hacking when I suddenly notice a clutch of shiny purple. Even as I cut it down, the plant offers me its gift – knowing I will take the fruits, and their seeds with them.

Here then is another way of proposing a vernacular appropriate to today: not simply to take what is readily available, but explicitly that which is overabundant, the removal of which supports diversity in those precious pockets where it still survives. And, in vulnerable places like the Lye Valley, to actually /put back/ and /hold back/.

So what would a palette of materials based on these fast-growing, watery plants be like? One thing plants have long been used for is papermaking. Before the advent of plastic, a surprising number of household goods were moulded out of papier mache – from trays to furniture, and even architectural mouldings. Its lightness and low cost saw papier mache replace plaster mouldings in some buildings, and a few eccentrics have been known to build whole houses from it. Importantly as it comes from the body of a living being it is biodegradable, with coffin making amongst its earliest known uses.

The Himalayan Balsam is a good candidate, as nobody objects to its complete removal even if this were to result in eradication. Its tough stalks are made up of sections bridged by vulnerable, fleshy joints which swivel and creak like my injured knee. I flex them gently, disturbed, wondering how much DNA we have in common. Its outer flesh is soft and malleable, and makes a half decent paper mix.

![Illustration of Charles Bielefeld's Improved Papier Mache architectural 'enrichments' [4].](https://fig.studio/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/papierMacheEnrichments1300px-800x605.png)

I also have some success mixing reed and sedge into a paper pulp along with recycled offcuts gathered from businesses in the area. As water-dwelling plants their flesh is slick and shiny, repelling water and refusing to gel much. Blades of green sit torn but untransformed on the paper’s surface. More friendly however is the ubiquitous willow, another plant known for its resilience against human outrage – even associated immortality, for its habit of rooting anew from the smallest cuttings. Its bark used whole makes a rough and ready papier mache, while the inner bark alone yields a beautiful pale pink material of almost felt-like delicacy. The water it’s boiled in is stained a deep oxblood red, reminiscent of cooked ochre.

Like the ‘immortal ochre’ ink obtained from flowers grown onsite, the future of vernacular papermaking surely lies in those plants which can be grown, coppiced and cared for on the allotment. Only here can we ensure we are giving back to the site as much as we take – with the seasonal addition, perhaps, of those ‘thugs’ just scythed. And so, from the context of the surrounding waterways I look to the allotment site itself.

Elder Stubbs already has an established vernacular in terms of those plants which are commonly grown. The meaning of the place has changed over time, increasingly acknowledging a role for spiritual as well as physical sustenance. The growing of flowers wasn’t always allowed, as it would reduce productivity. I speak to one allotment holder who remembers this rule being changed. Now, sunflowers are one of the most familiar plants there. To get to know the resident plants and people better I run some worshops with Restore’s Elder Stubbs recovery group who are based at the allotment. I bring a wheelbarrow full of my various pulps and inks gathered on my wanderings. They in turn show me round their large and established plot, where they produce eggs, flowers, vegetables, and a vast compost heap whose grass cuttings when cooked yield a delicate paper. Together we experiment and play with these unfamiliar new materials, and go foraging around the plot to find more. Their hens give us eggs, whose whites fortify our papier mache mix with a tough glossy sheen. The faded sunflower plants give us pulpy flesh which we sculpt into shapes and sheets. In the process of mixing and cooking, the group discover a striking blue dye from the discarded sunflower seeds. Kept in the dry, they will last a little while. But even after a couple of weeks, blue mould starts to appear on their surface.

As the November nights draw in, the final stage of the project sees us gather all these offerings together and ritually put them back to compost. They include objects made by Restore group members, and attendees at public workshops. I’ll never know the precise meaning of each one, though some of their makers have hinted at them: a secret prayer, written in vegetable ink and concealed in clay. A ball of intense emotion bundled up ready to give away to the soil. Others are simple experiments, testing the contours of materials gathered nearby. By this time next year, they will all be gone. This new compost heap will go onto the Fig project’s allotment, providing nutrition for whatever projects come next.

You are welcome to join us at this closing ritual, which will take place at Naturescape, Florence Park on Sunday 7th November 3-4pm.

Click here for more information.

[1] Environment Agency (2021), Flood Risk Map

[2] Friends of Lye Valley (2021), About the Lye Valley

[3] Oxford Urban Wildlife Group (2021), Get Involved

[4] Charles Bielefeld (1850), On the Use of Improved Papier Mâché in Furniture, in the Interior Decoration of Buildings, and in Works of Art